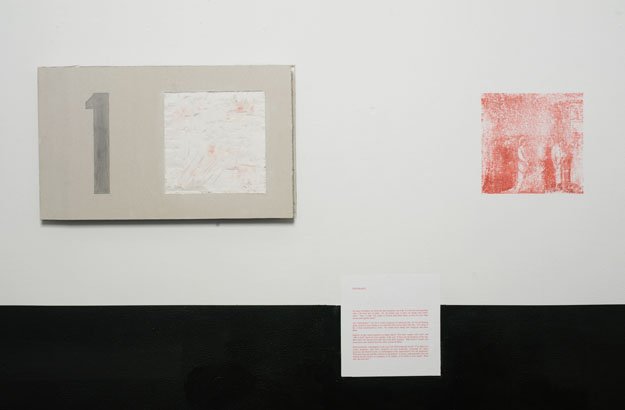

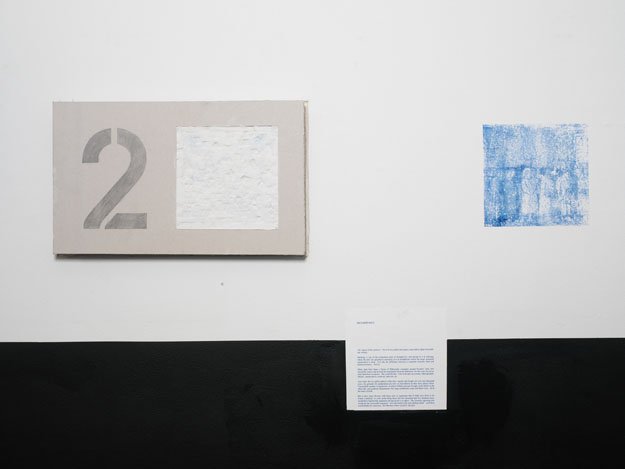

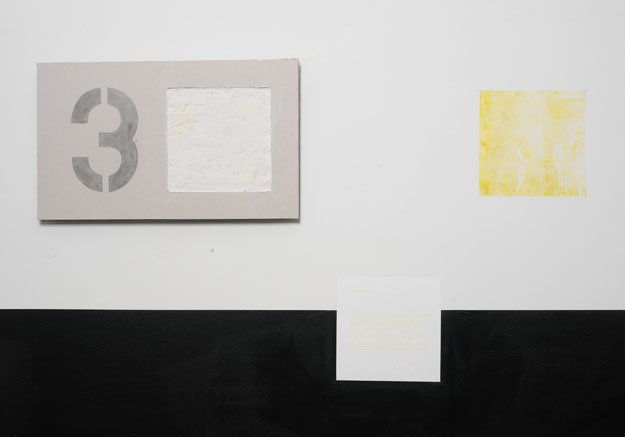

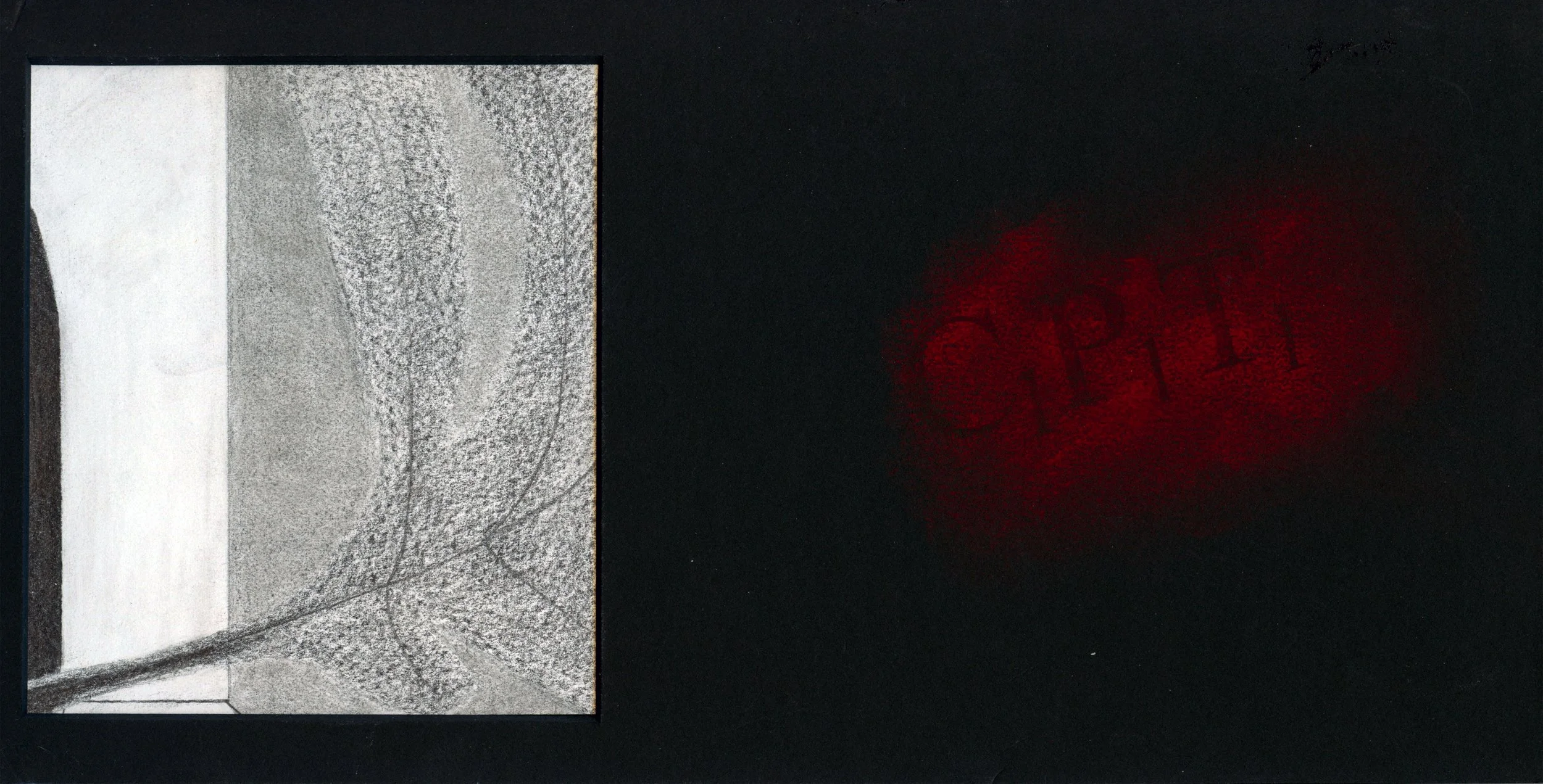

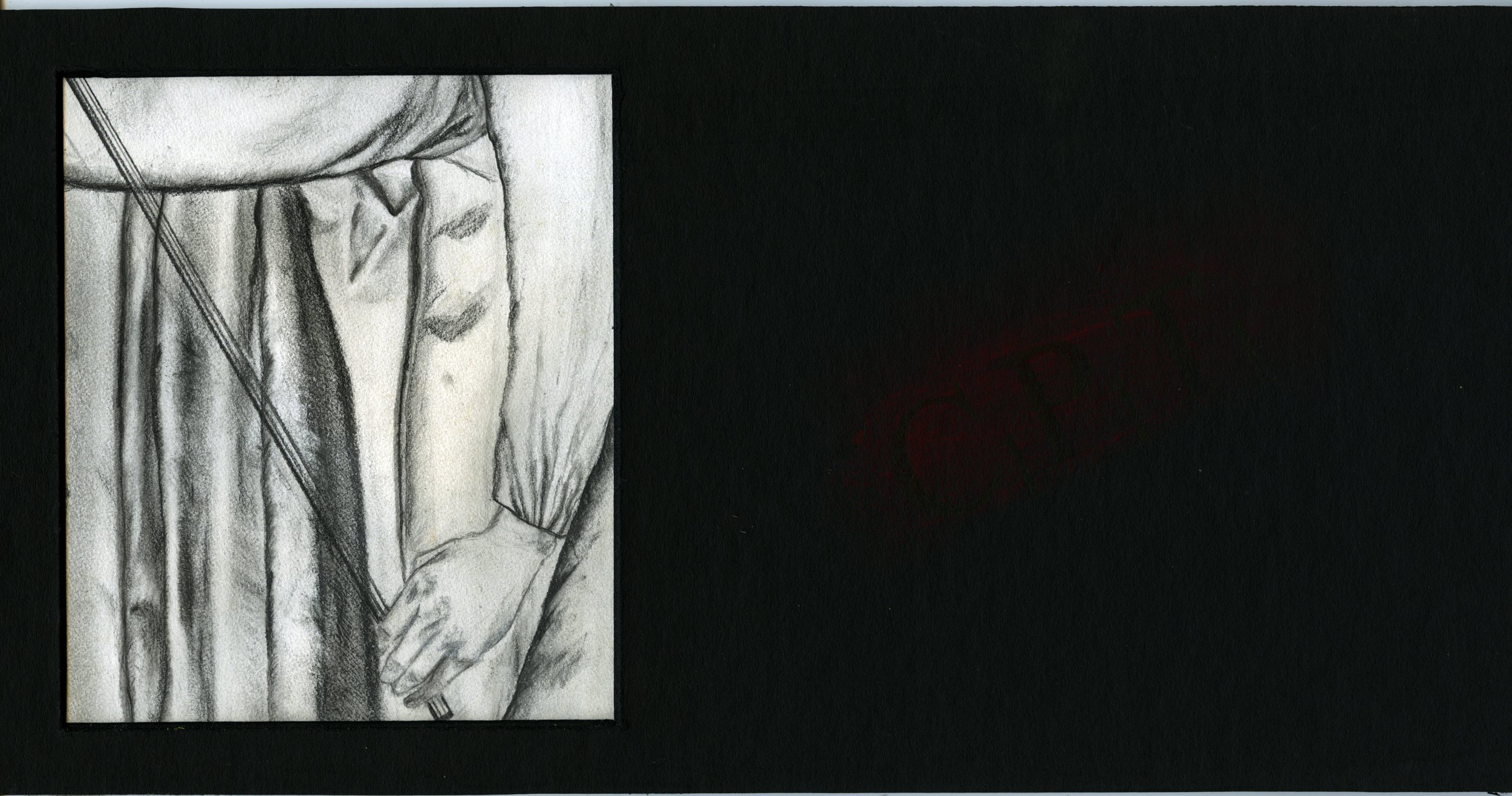

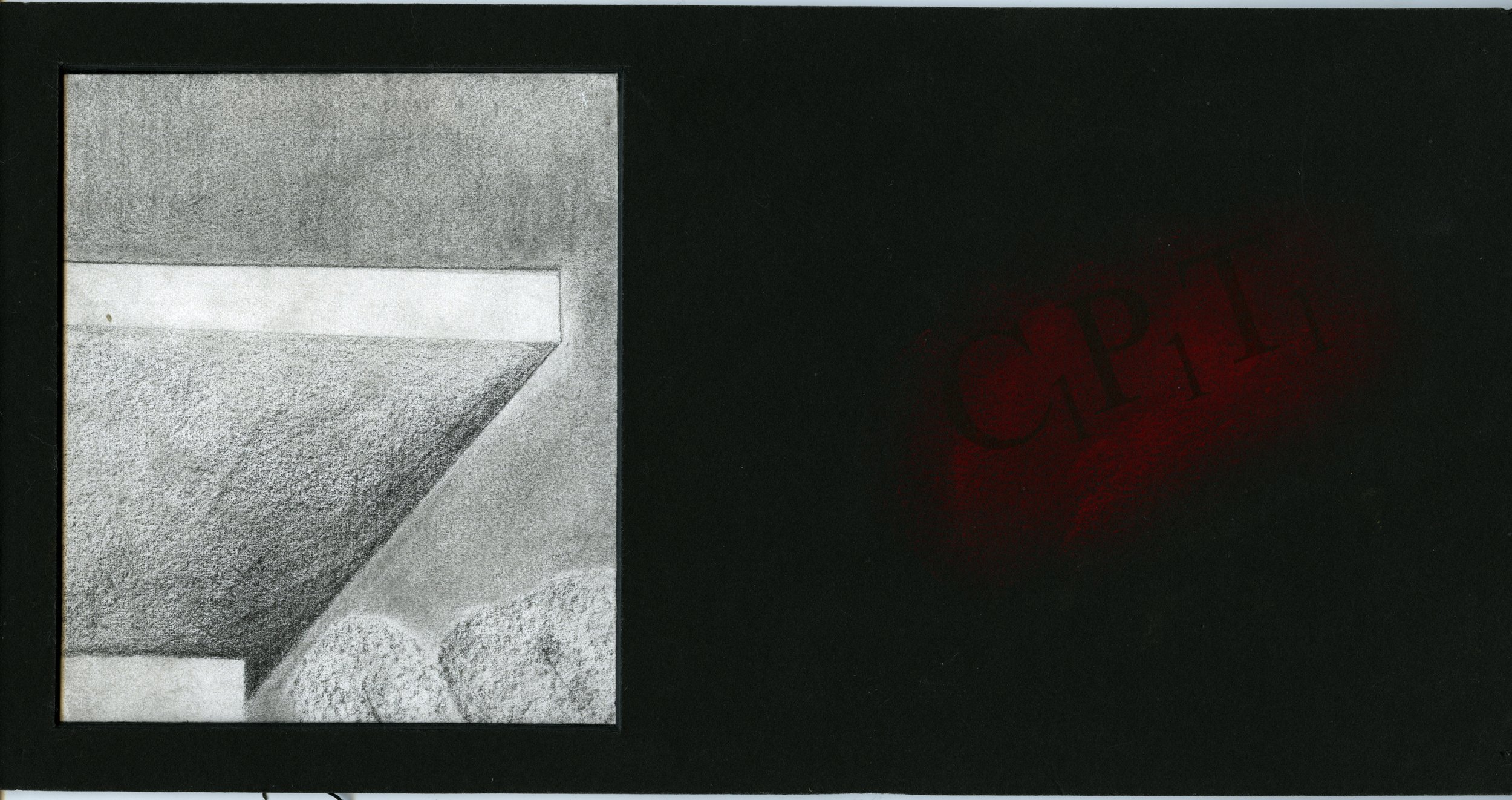

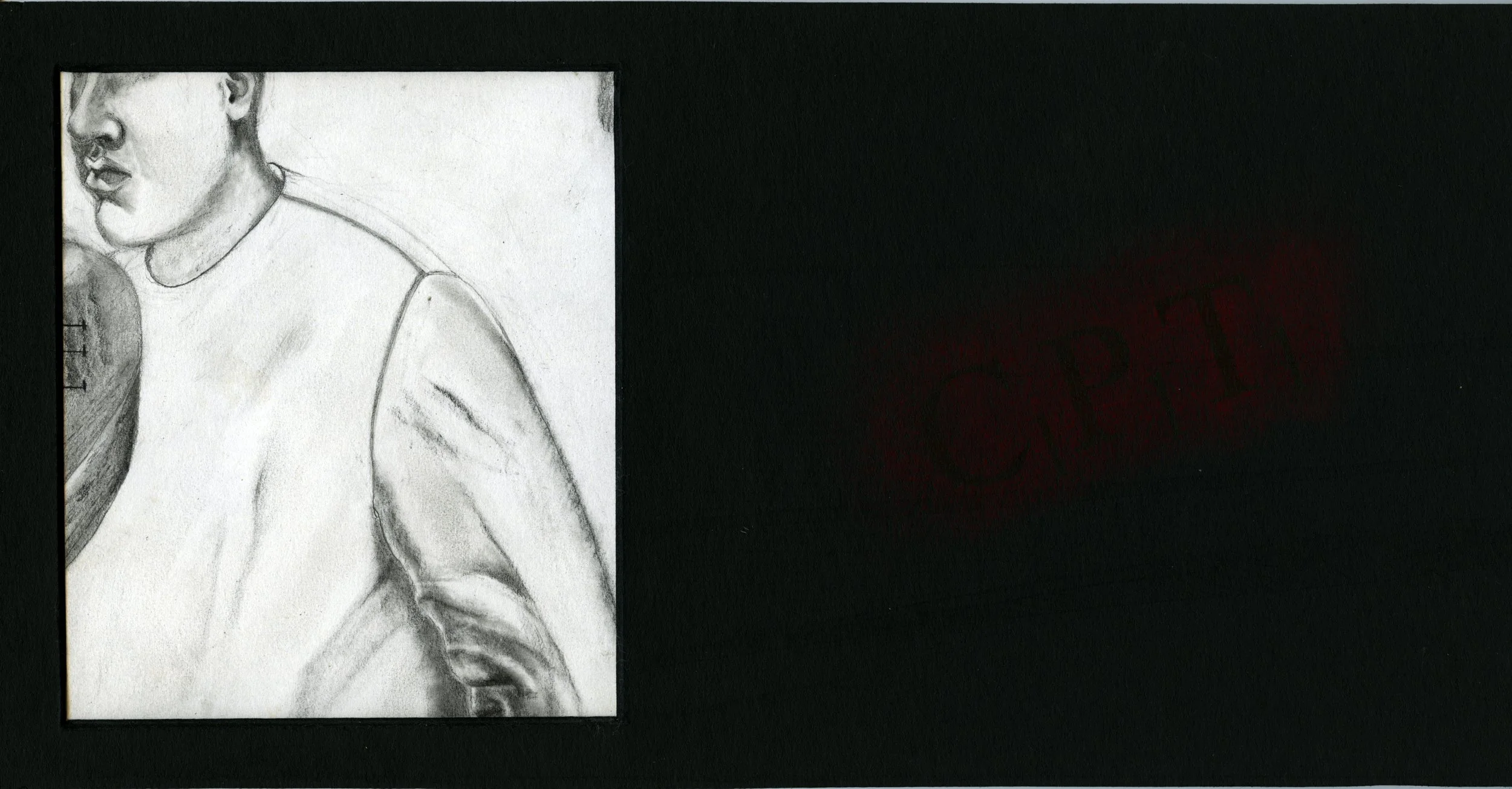

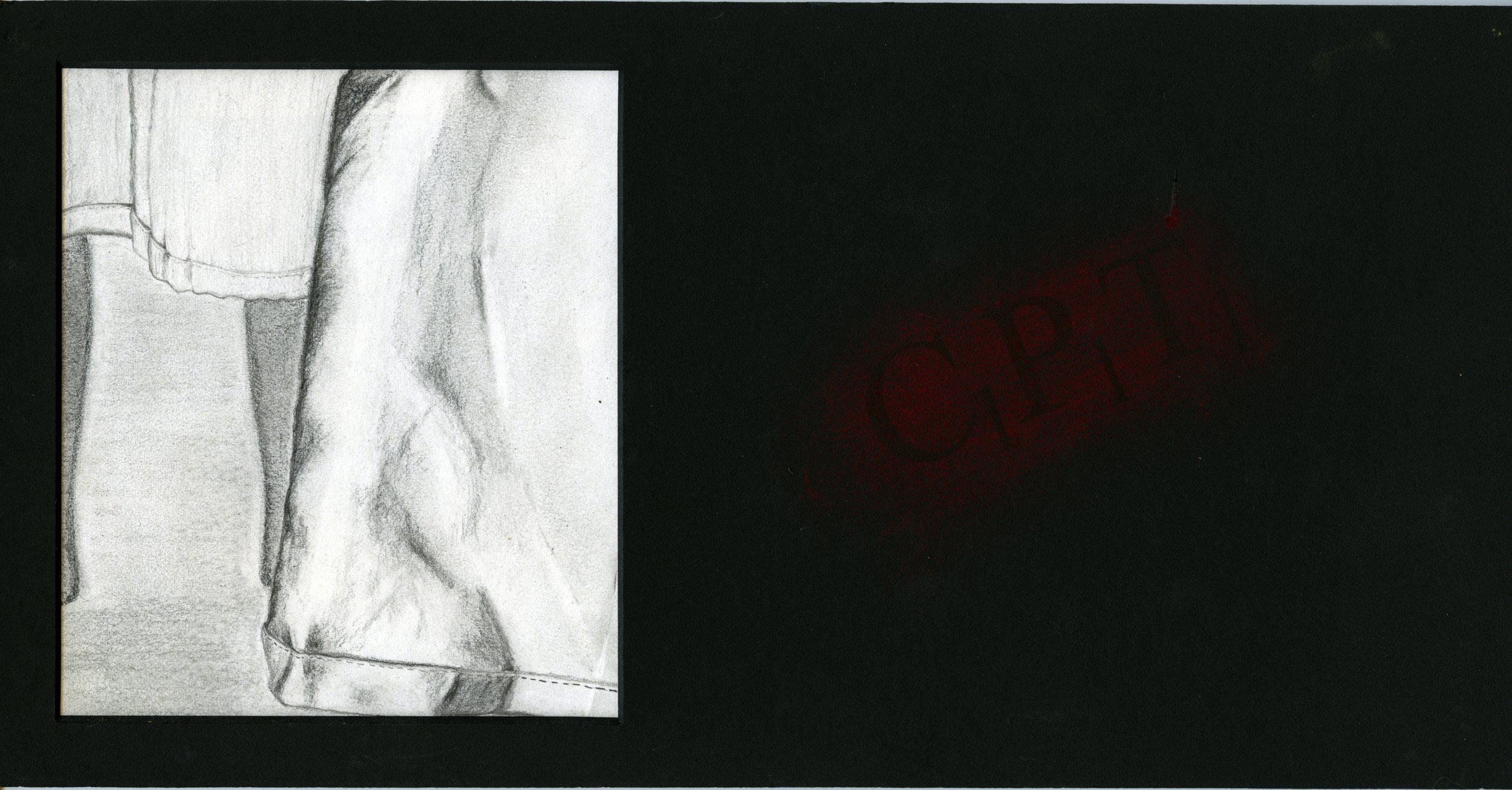

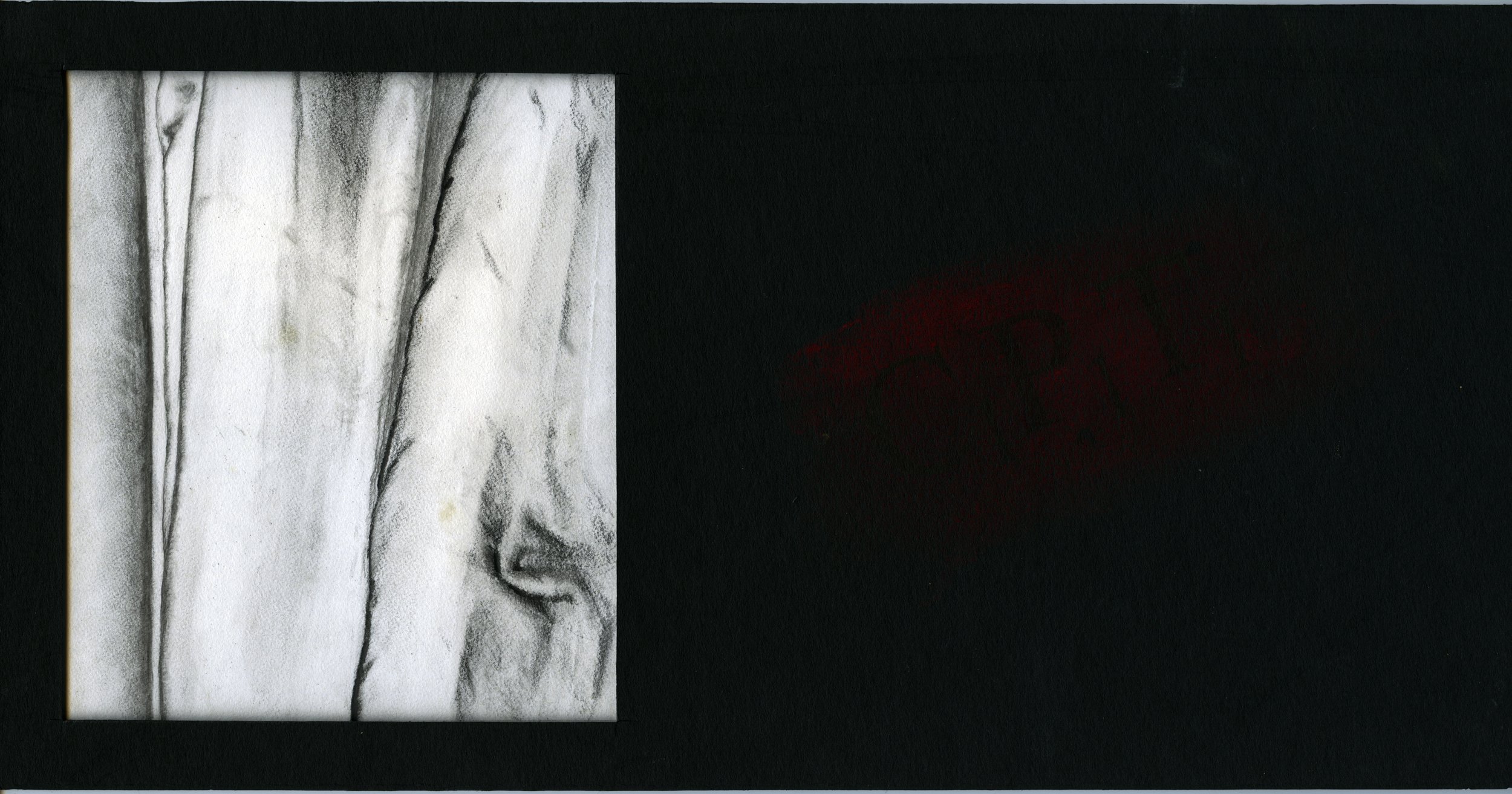

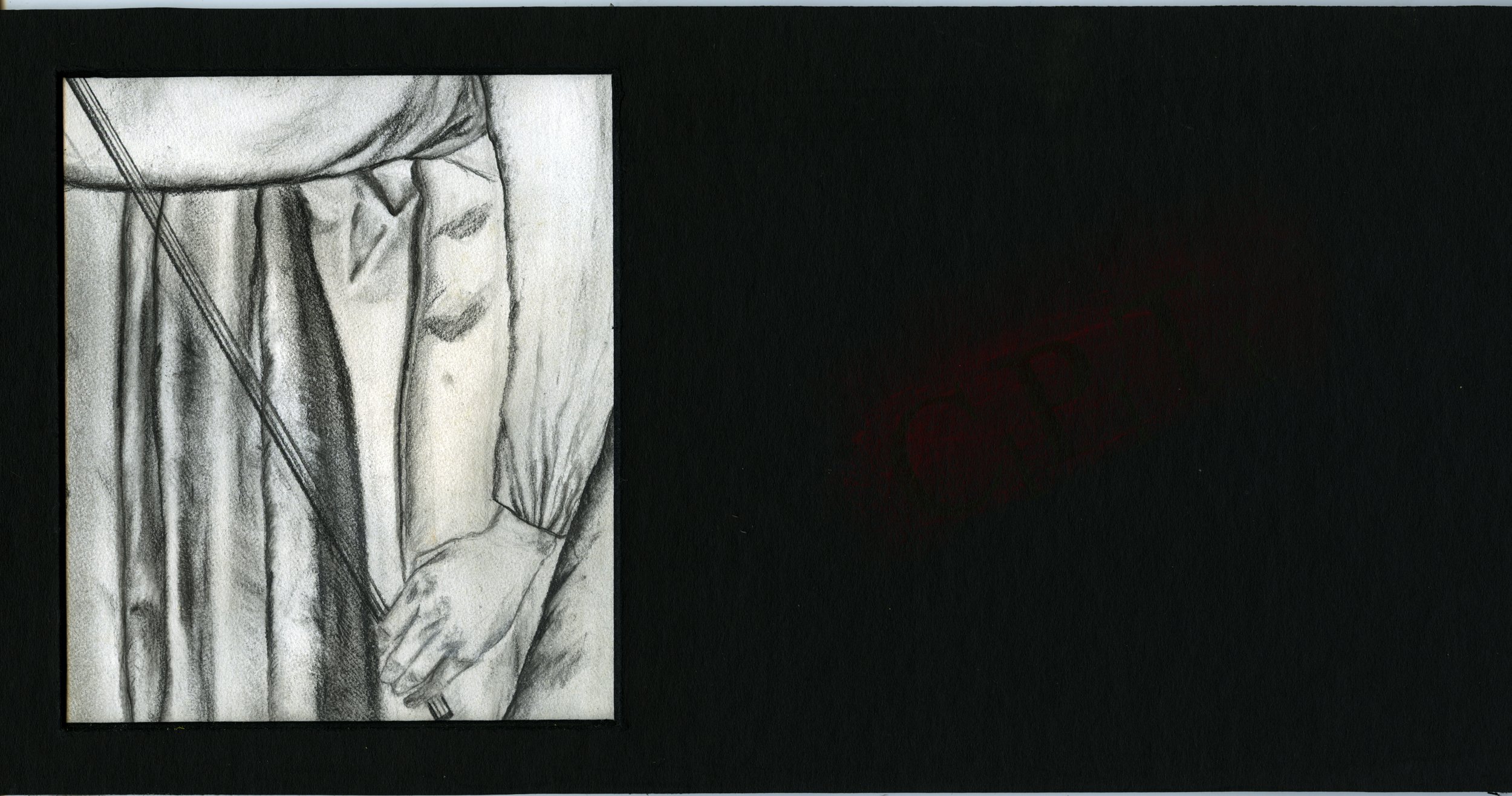

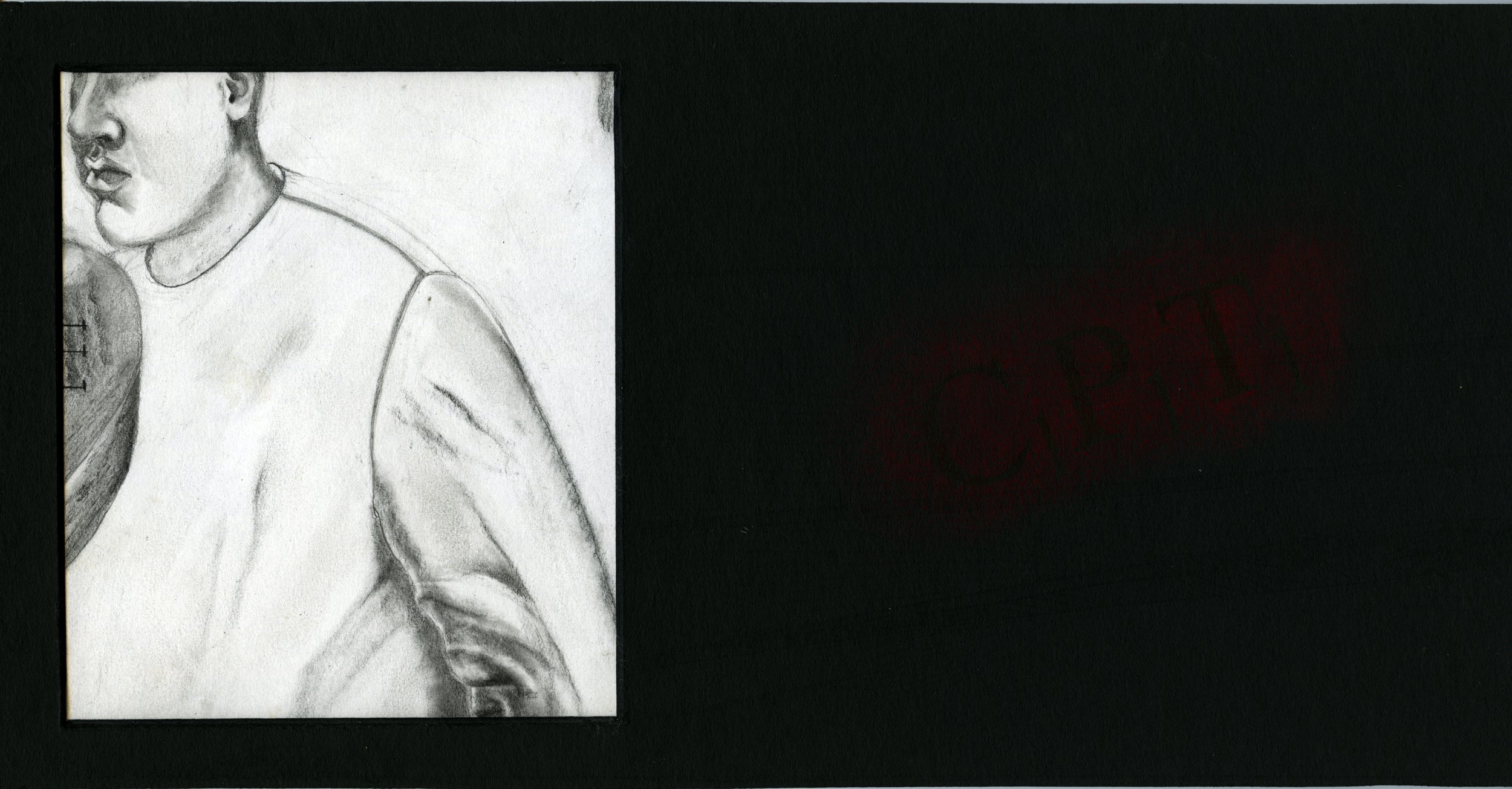

The VISUAL (Artworks)

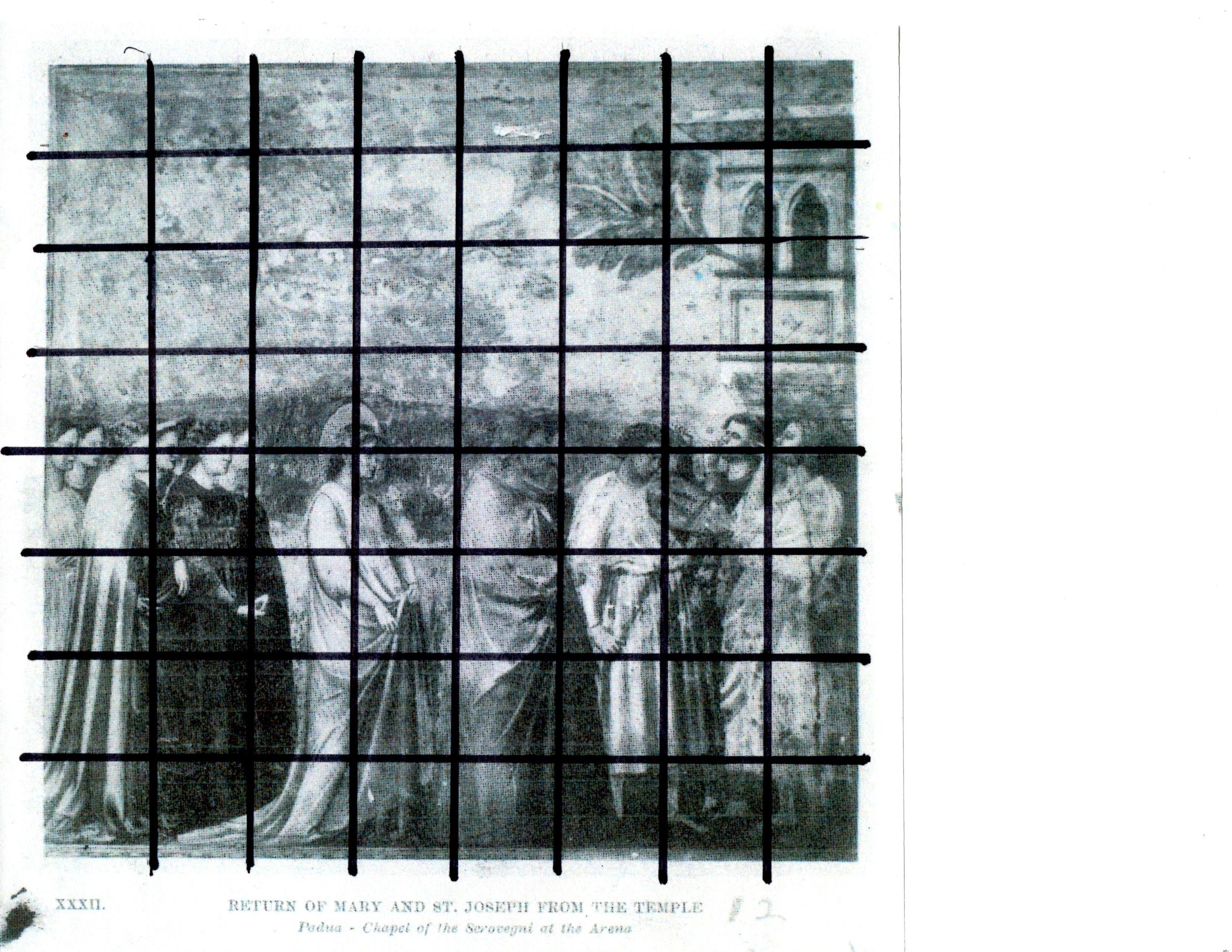

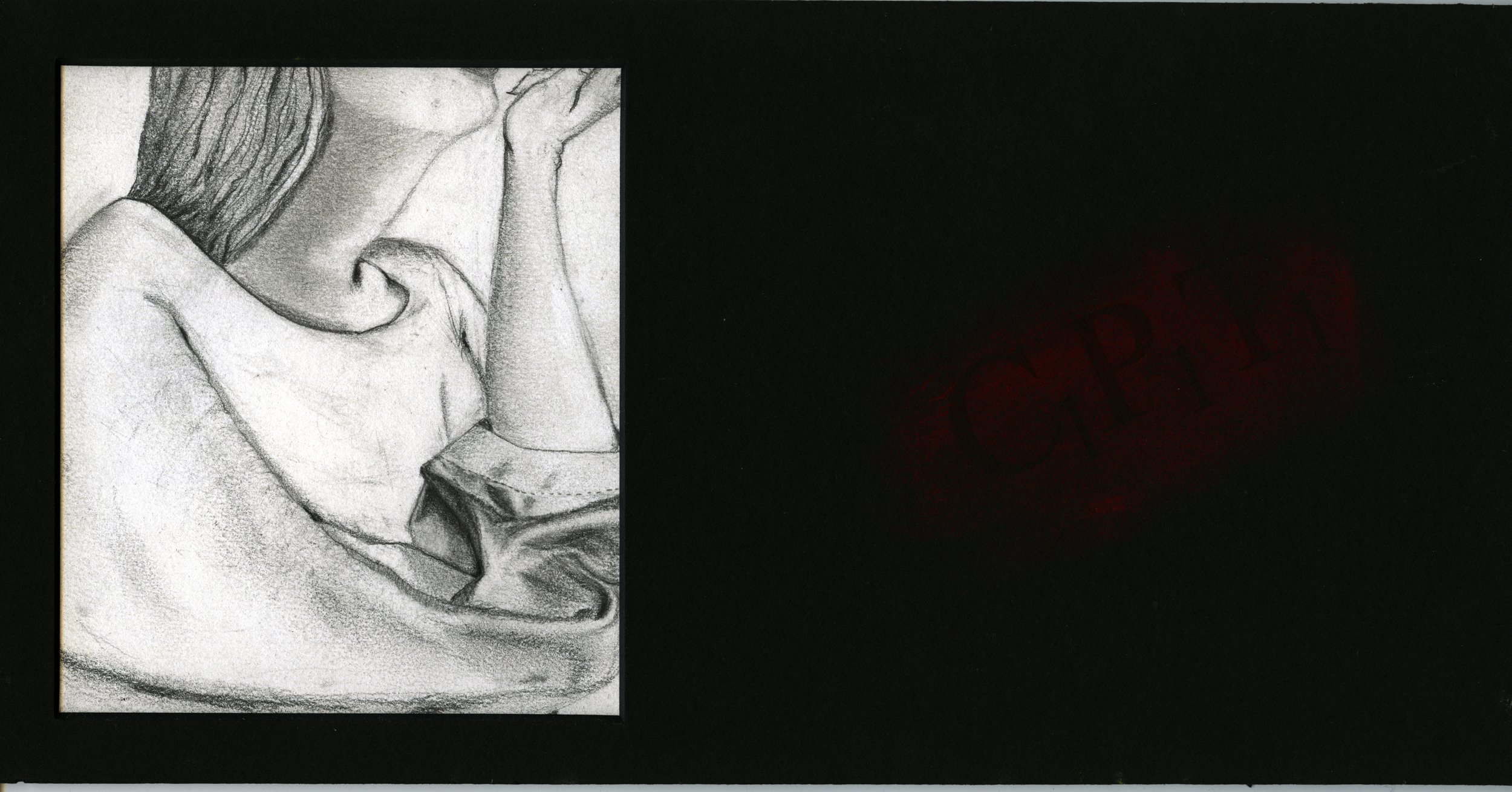

GIOTTO di Bondone (b. 1267, Vespignano, d. 1337, Firenze)

No. 12 Scenes from the Life of the Virgin: 6. Wedding Procession

c. 1304-06

Fresco

200 x 185 cm.

Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua

ARTIST’S STATEMENT (2024)

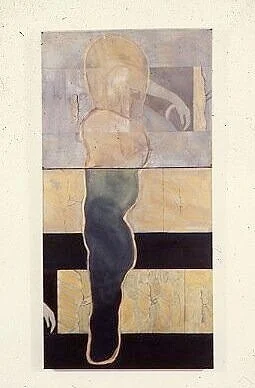

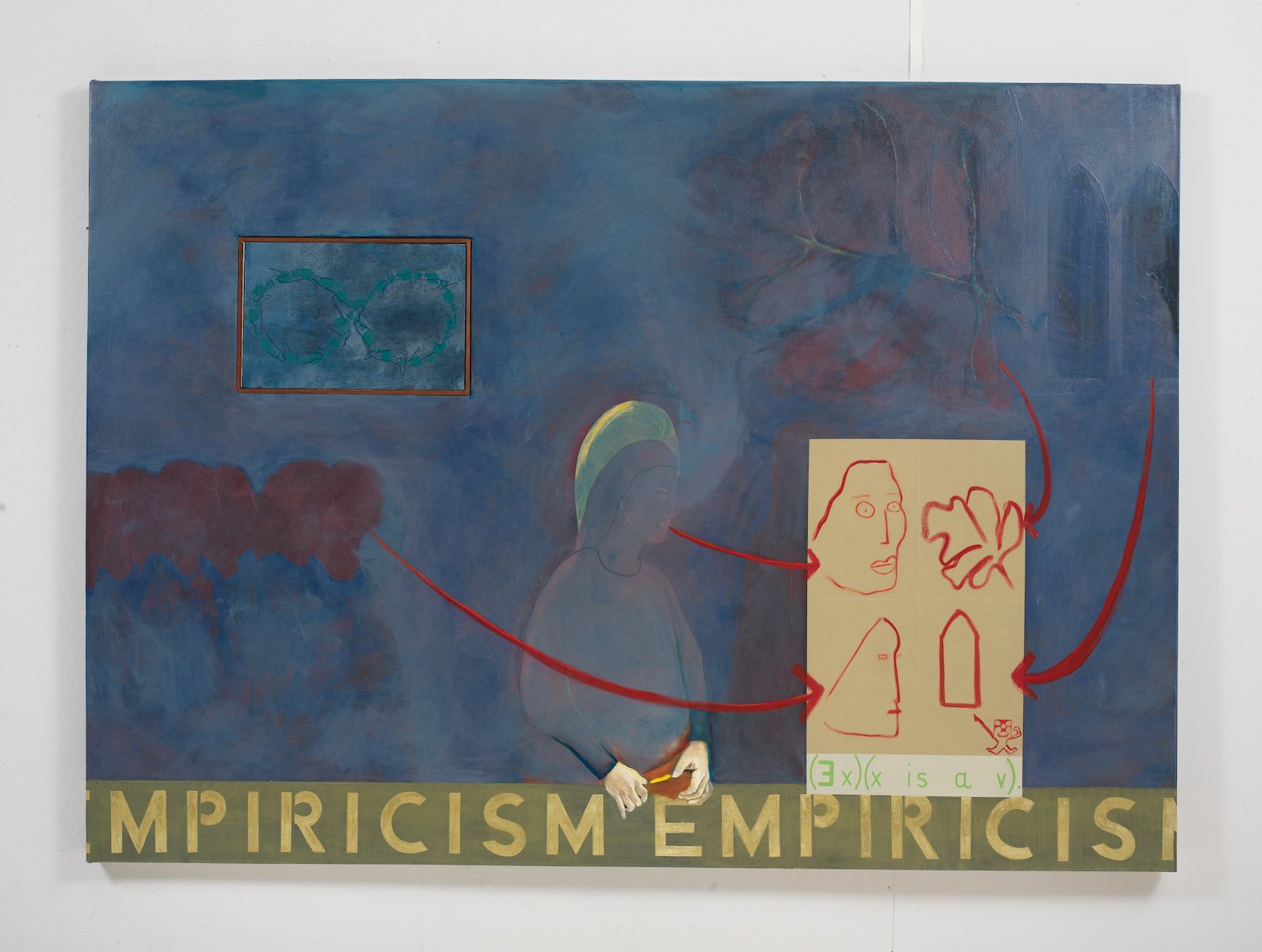

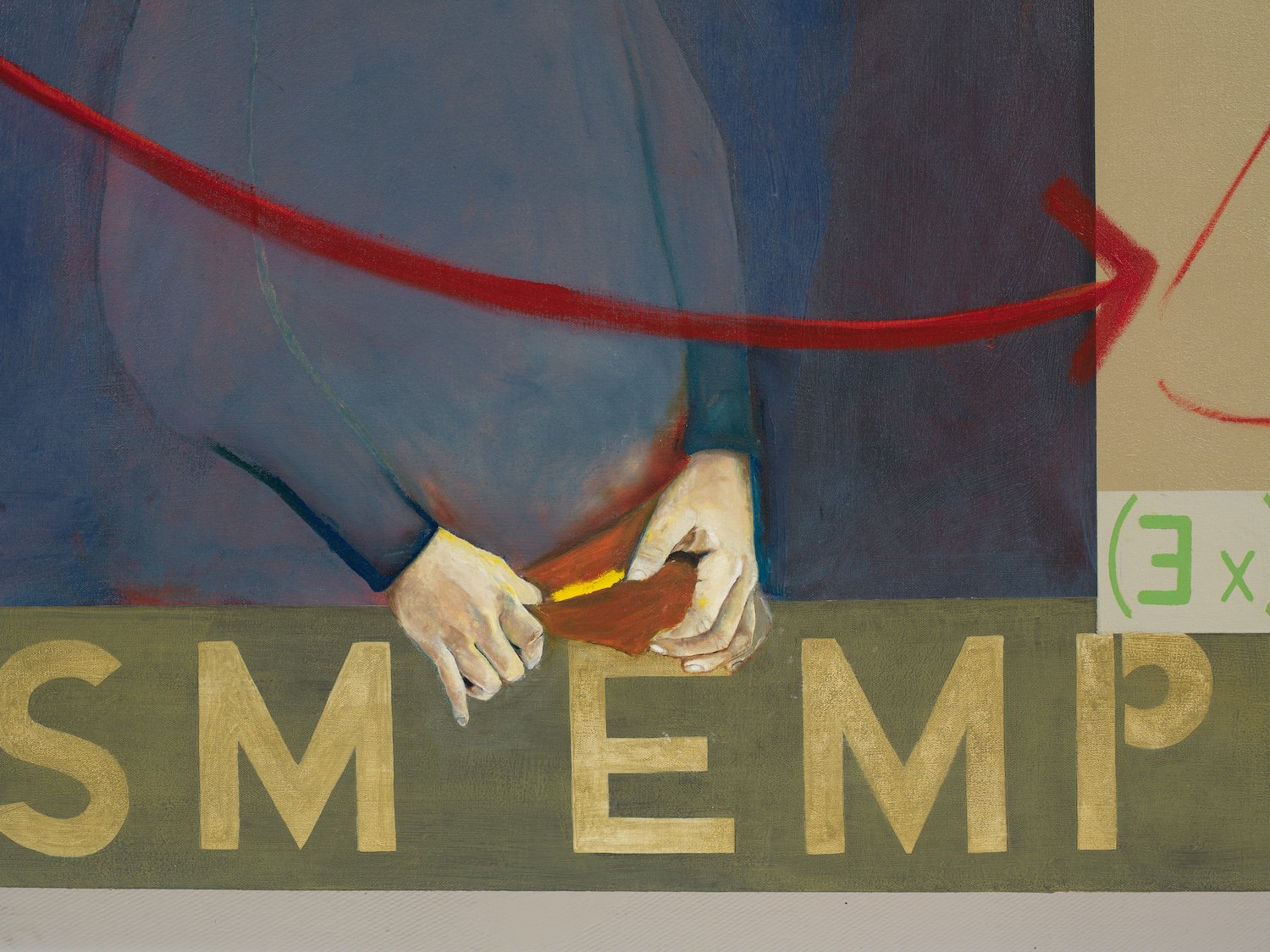

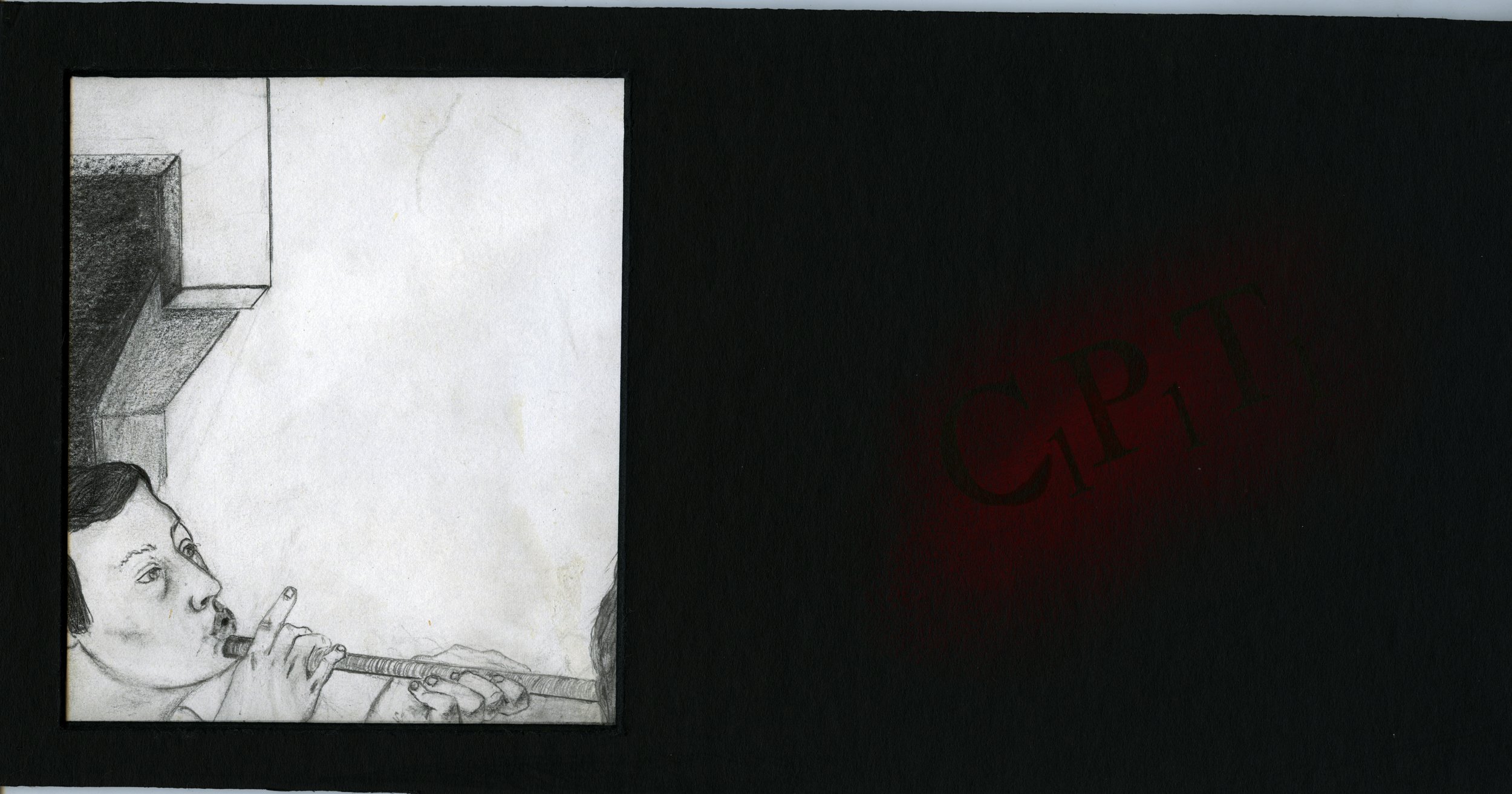

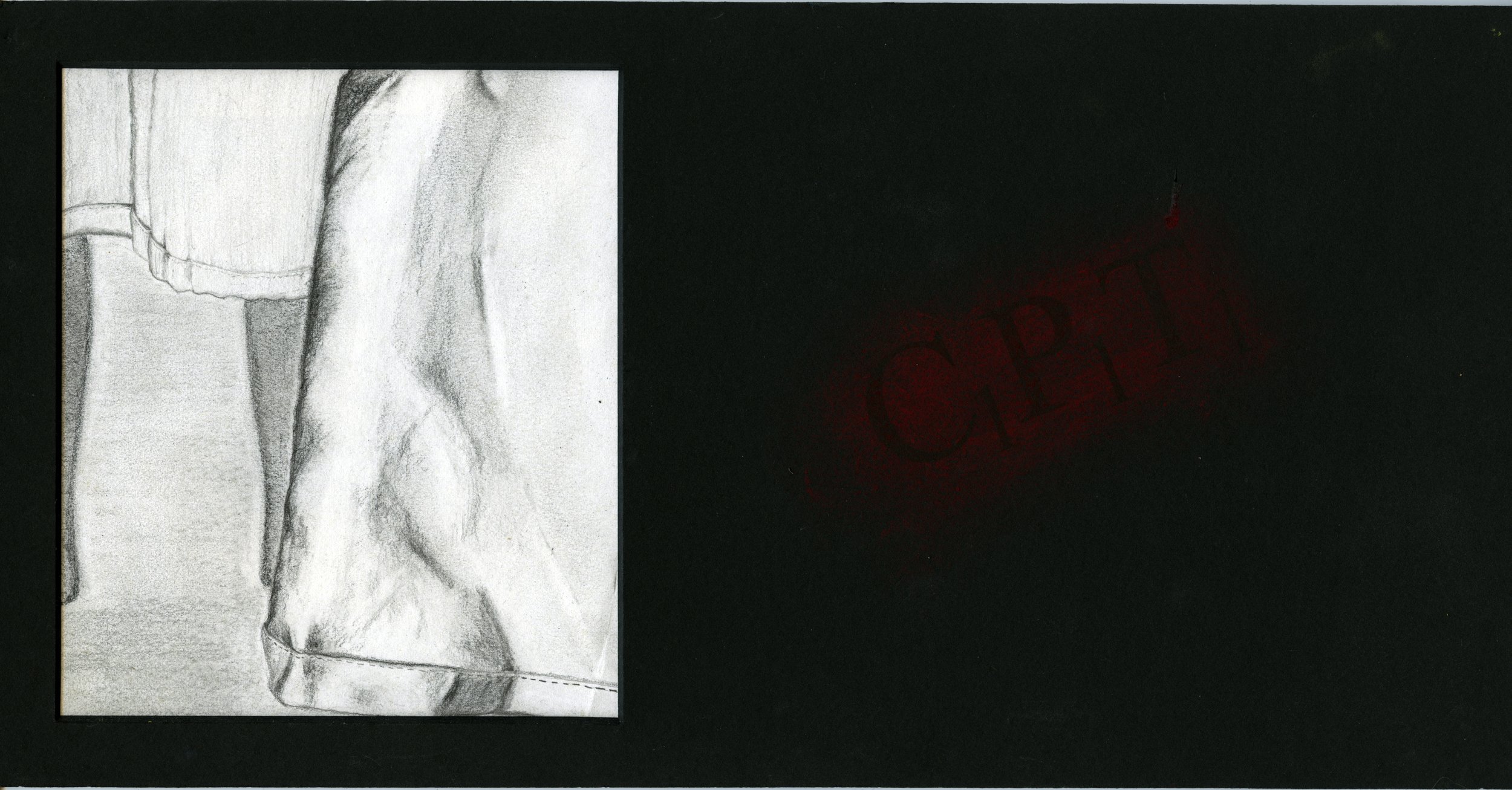

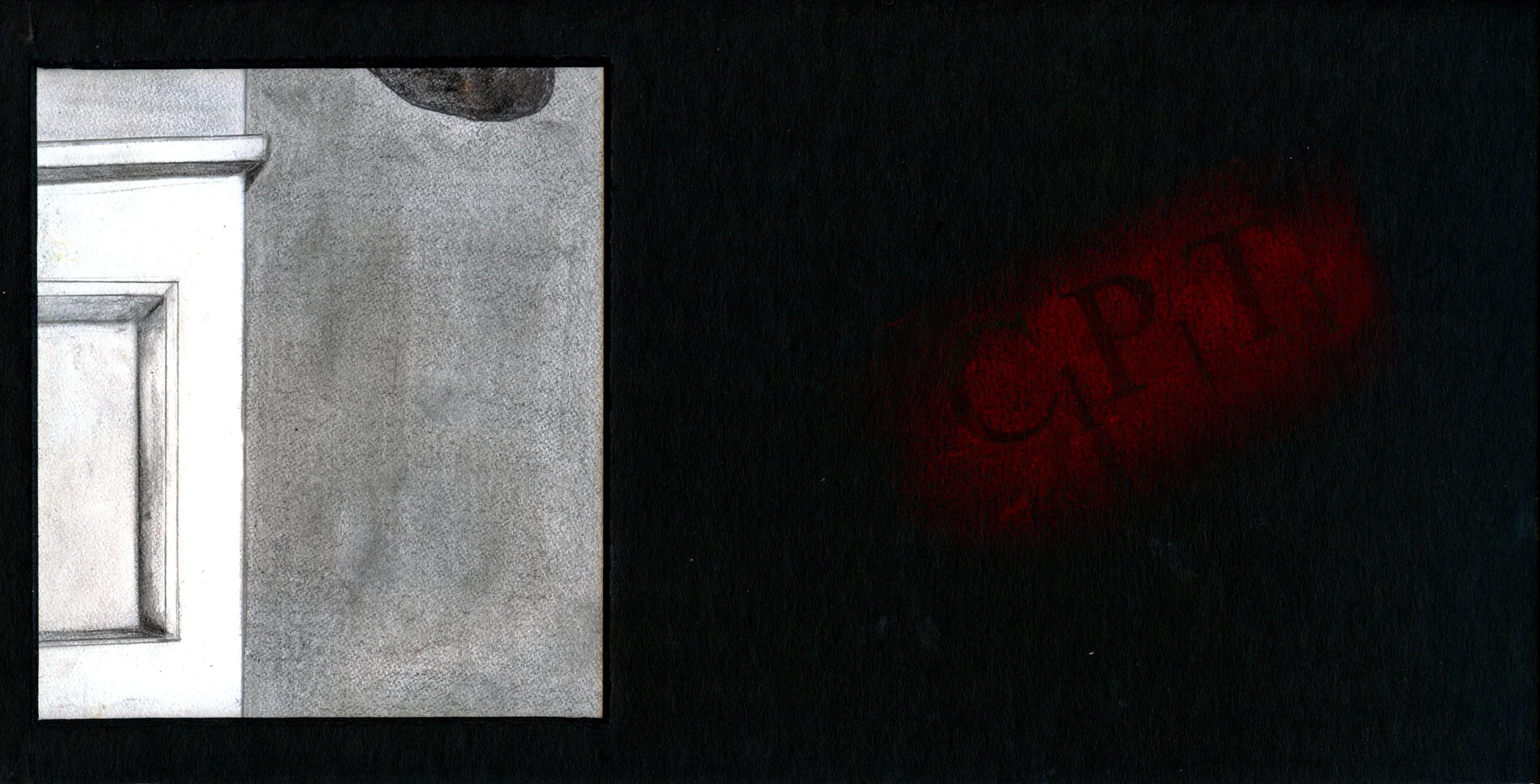

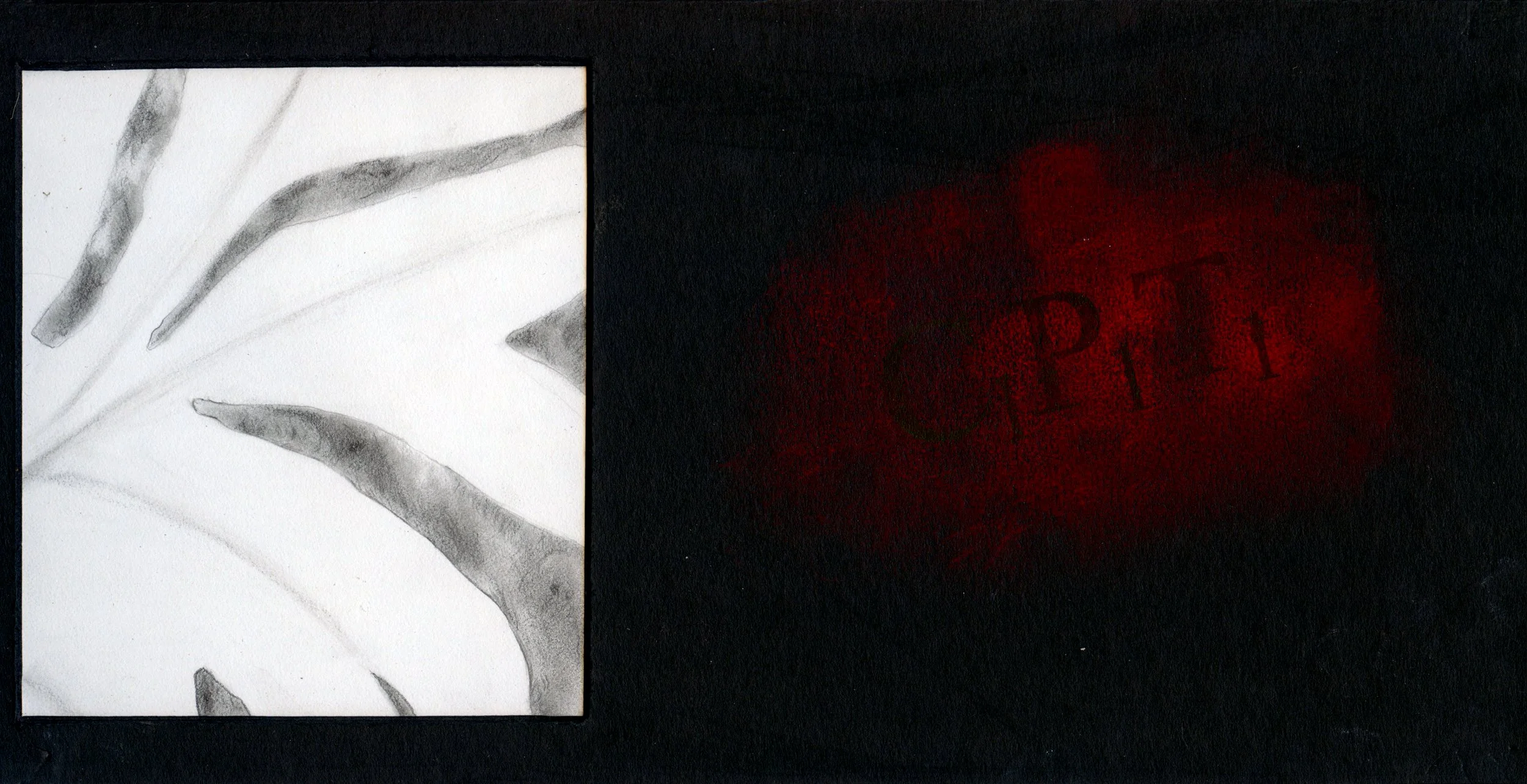

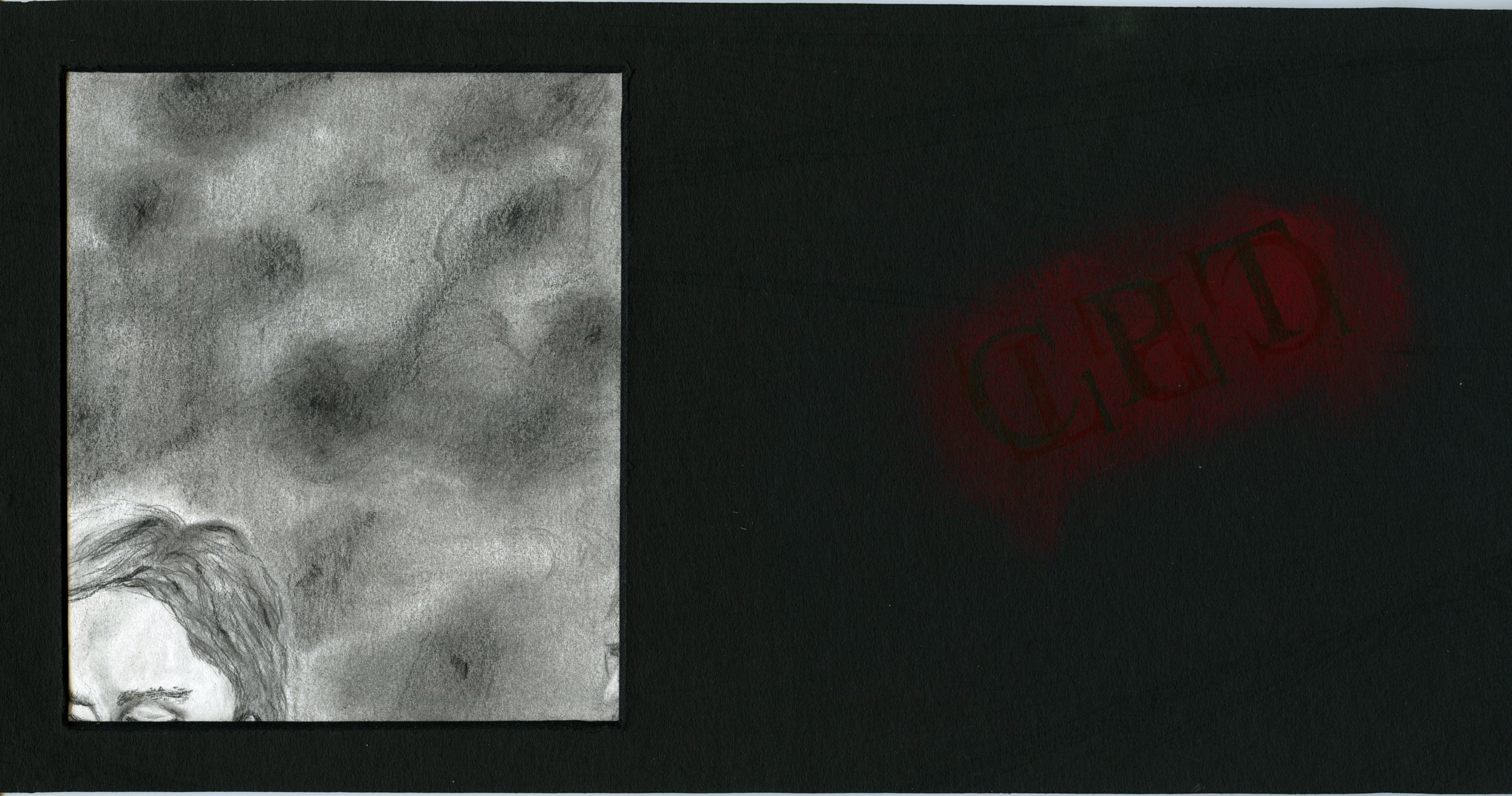

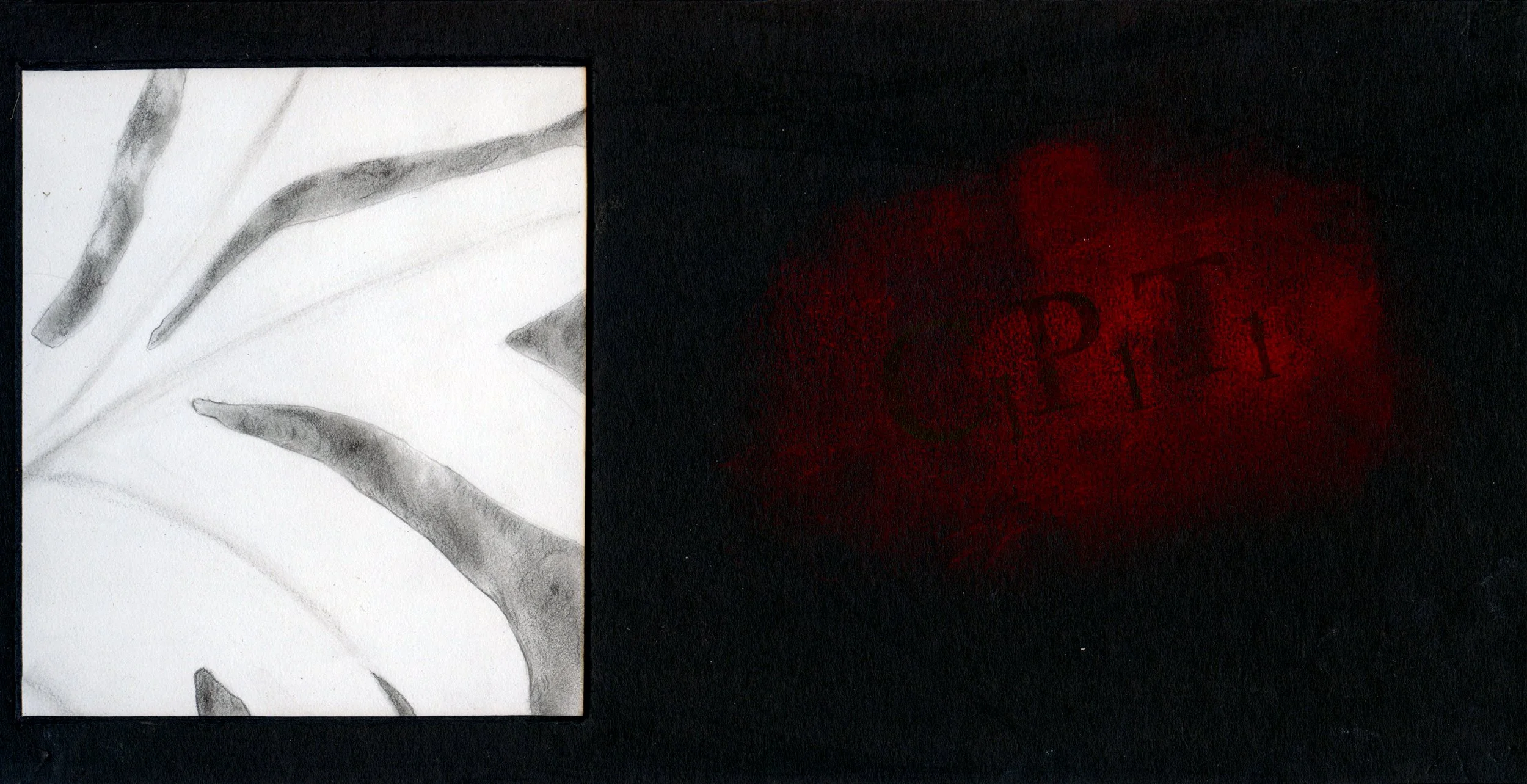

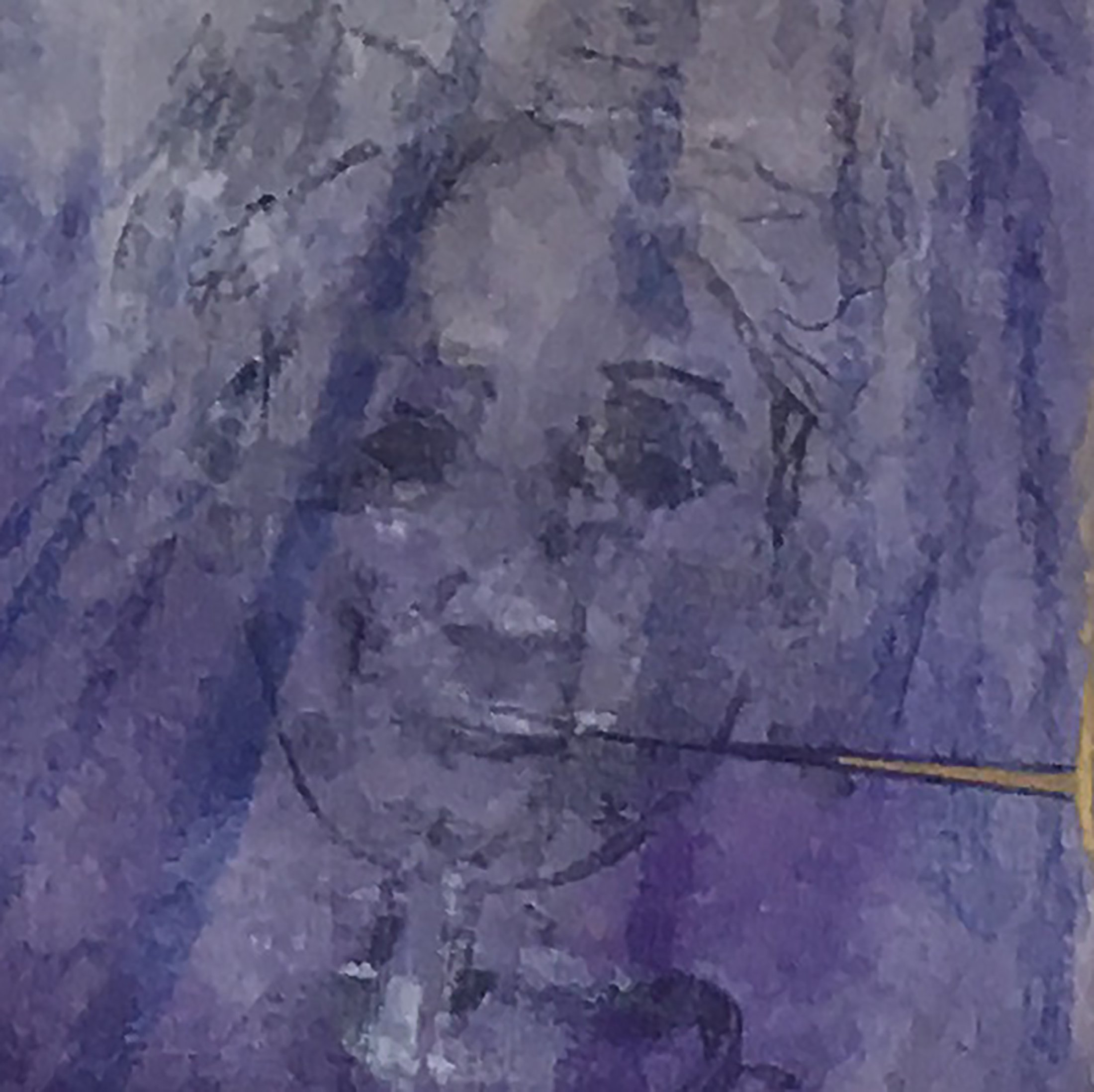

My work is about philosophical investigation. And the transcendence that follows. I have used only one image, Giotto’s The Marriage, for over three decades, painting it each time in different, edited ways thereby revealing the multiplicity that lies within both visual experience and thought. Every visual experience and every thought has many, many perspectives that could be chosen, and using the one image is a way of investigating that fact. For the past decade, the additive modalities of conversation and text have been applied to the (nested) investigation of a particular philosophical topic, under the umbrella of the nonprofit talkPOPc (Philosophers’ Ontological Party club). The public, in-person conversations (MC’d by our mascot puppet Popsey!) then open up this topic to others and the generating consensus is the culmination of the investigative urge. Quotes from the conversations get shifted back into the artworks in the form of printed words on rolled paper, a device that allows viewers to delve and pry for themselves, revealing the social nature of investigation.

Work 2011 - Present

Performance: The Philosophy of Plumbing @ Trade School at The Whitney: A Coincidence of Wants, 2011

On typical Friday evenings, admission to the Whitney is “pay-as-you-wish,” but on March 25, certain visitors presented a more tangible form of payment. For the public program Trade School at the Whitney: A Coincidence of Wants, participants brought objects of their own creation in exchange for enrollment in one of sixteen quirky courses held simultaneously throughout the Museum. The curriculum varied wildly but all of the courses were based on creative and artistic themes.

Trade School, a collaborative that coordinates instruction for barter, offered sixteen courses at the Whitney, March 2011. Photograph by Tiffany Oelfke

Once visitors dropped off their barter items (which ranged from framed photographs to homemade beet muffins), they gathered in the Whitney’s Lower Gallery, waiting for the first class bell to ring. In one small corner, students huddled around philosophy professor Dena Shottenkirk, who examined plumbing techniques through a philosophical lens in “Philosophy of Plumbing from Kant to Kierkegaard.” Meanwhile, within earshot, 10-year-old Quinn Accardi taught “Comics and Cartooning for Everyone” to twenty students, some more than fifty years his senior.

250 students enrolled in Trade School at the Whitney. Their tuition? An object they had created, March 2011. Photograph by Tiffany Oelfke

From “Pilates in a Chair” in the bustling lobby, to “Elevator Reanimation: The Brain and the Experience of the Divine,” a philosophy course that began—where else?—in the Whitney’s enormous lift, each course sought to engage and activate the interstitial spaces of the Museum. Some courses, like “Present-Time Feng Shui,” directly employed the Whitney’s renowned Breuer building, teaching students how to clear energy and spaces while walking down the staircase, while others, such as “Monday Painter/Sunday Banker” navigated the economic space of art and commerce.

Two of the hardier courses took place outside, in the museum’s “moat.” Here students learn how to make their own spectrometers with members of MIT Public Laboratory, March 2011. Photograph by Tiffany Oelfke

As the final bell rang, instructor Amy Whitaker presented her last PowerPoint slide. Its quotation by Adam Smith proved an apt end to an evening of bartering, learning, and creative commerce within the walls of an evolving institution: "A work of art is a new thing in the world that changes the world to allow itself to exist."

PERFORMANCE TRANSCRIPT:

[demonstration] The parts used by plumbers are provocatively named. Nipples, male connector, female connector, elbows (for the adventuresome). All empirical, real. And yet hidden behind walls.

So it is with both Kant and Kierkegaard. Not the provocative part – that is not our analogy. It is the quality of being hidden that is the same. Kant’s philosophy’s (a reaction to David Hume, who, in Kant’s words, “awoke me from my dogmatic slumbers”), depends on the hidden, the presumed. Hume developed a strict empiricist philosophy wherein necessity was relegated to the tautological and unimportant. Reality was the empirical impression – the body’s registering an event – and the idea was merely the recording of that, a recording doomed to progressive deterioration and loss of “vivacity”. Kant reacted with horror.

[demonstration] This is how a sweat joint is made. This is what will be part of the invisible world – the plumbing behind the wall.

The Critique of Pure Reason was Kant’s answer to this, and it is from this that any philosophy of art must draw, and not the Critique of Judgment though the latter is his aesthetics. But his aesthetics is generally thought to be less radical, particularly as Kant did not especially like art and was modeling his aesthetics on an appreciation of nature. It is the distinction made in the Critique of Pure Reason between the noumenal world (the world that must exist as the necessary ground of all our empirical experience) and the phenomenal world (the world we call “experience”) that is more crucial to an understanding of the aesthetic experience. It is always the ontology that counts.

Kant distinguished between an objective world and our subjective path through it. My sensible body, my “I”, relates to the world as a subject distinct from my perceptions. The important question that he asked was: how much does the world owe its character or its existence to the human mind? Or, as a twentieth century analytic philosopher [such as Nelson Goodman] might phrase it: how much do our minds construct what they see?

Kant argues that all I empirically see is dependent on my ability add the phenomena of space, time, and causation. They are not in the objects, they are in me. Thus, the noumenal objects exist independently of space and time – exist in the noumenal world. Where are those things-in-themselves/that invisible world?

Kierkegaard knew too of an invisible world but it was a world constructed by faith and attained by embracing “the subjective truth” – not the objective truth of science. We have a right, he claimed, to be happy and to be free. We have a right to believe. In the unseen.

Art though is the visible. And if we have the most important world designated as invisible, then we have trouble explaining how art traffics between the visible and the invisible. Assuming of course that’s what we want it to do. Because if it’s not mining the most important part of existence, then what can it claim to do?

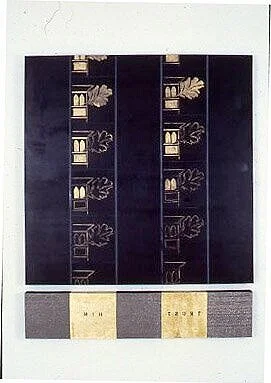

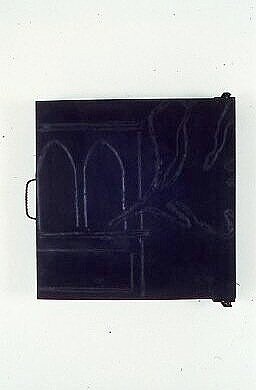

Work 1982 - 2010

Artwork 1980s

Artwork 1990s

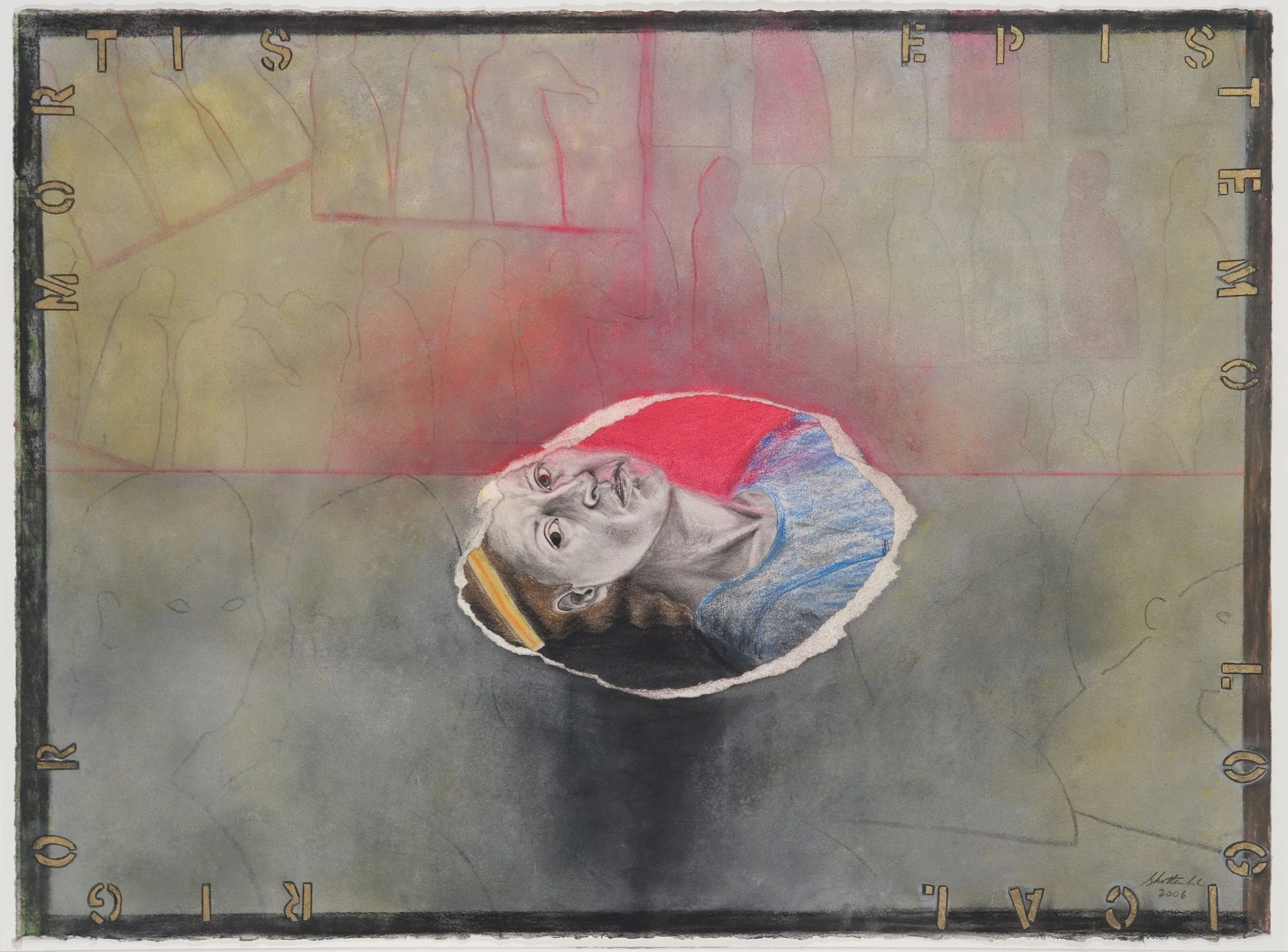

Artwork 2000 - 2010

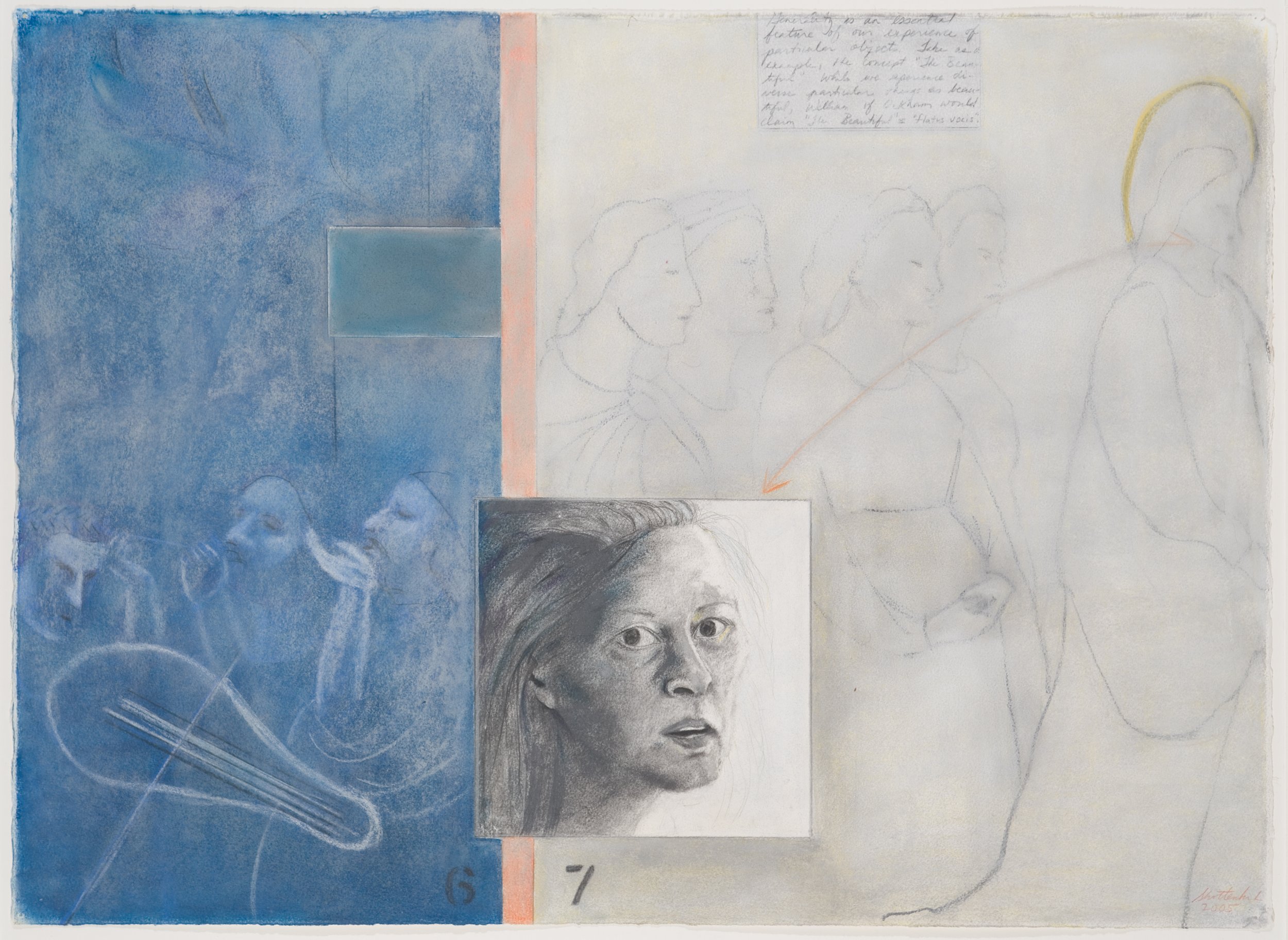

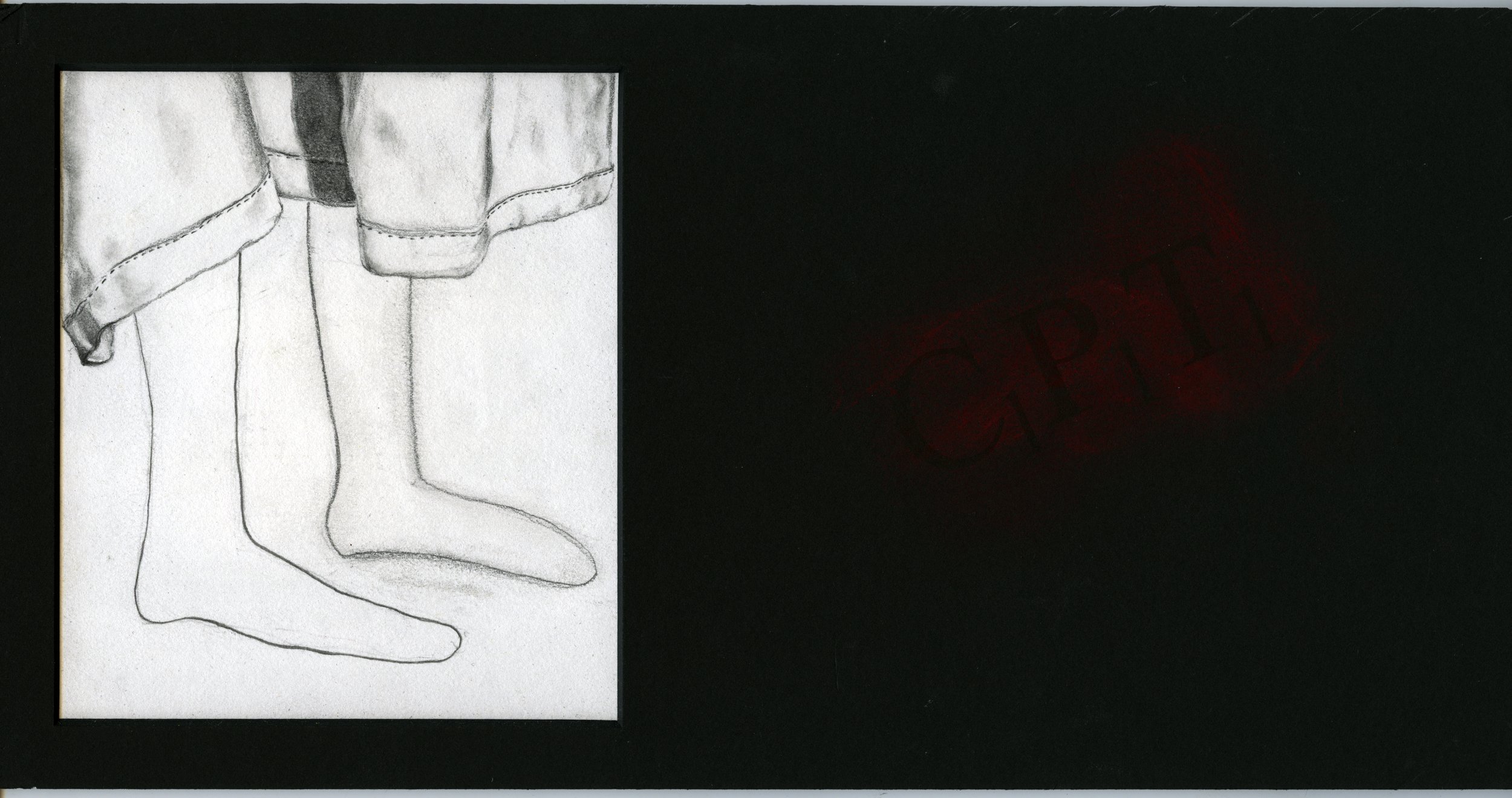

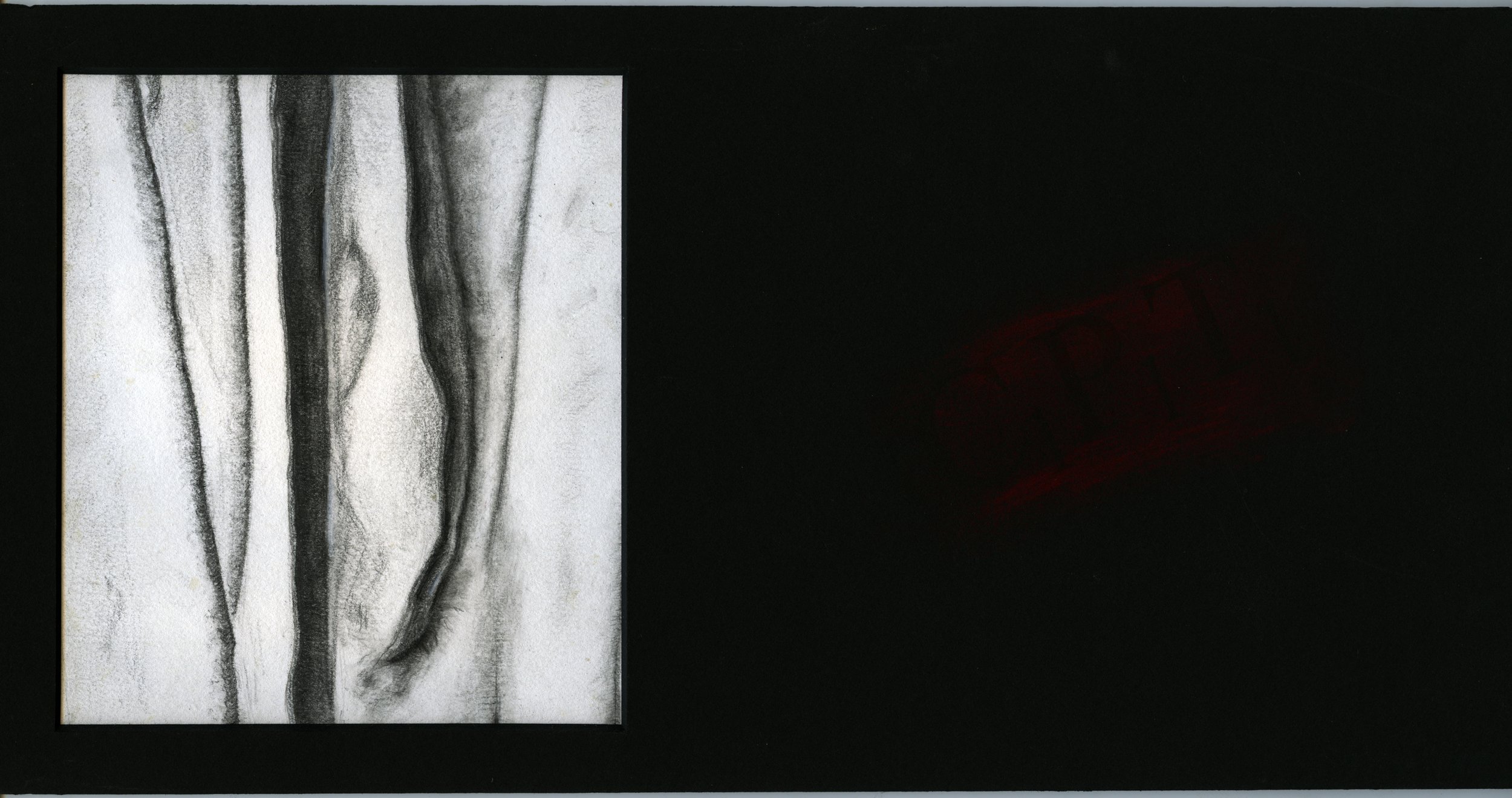

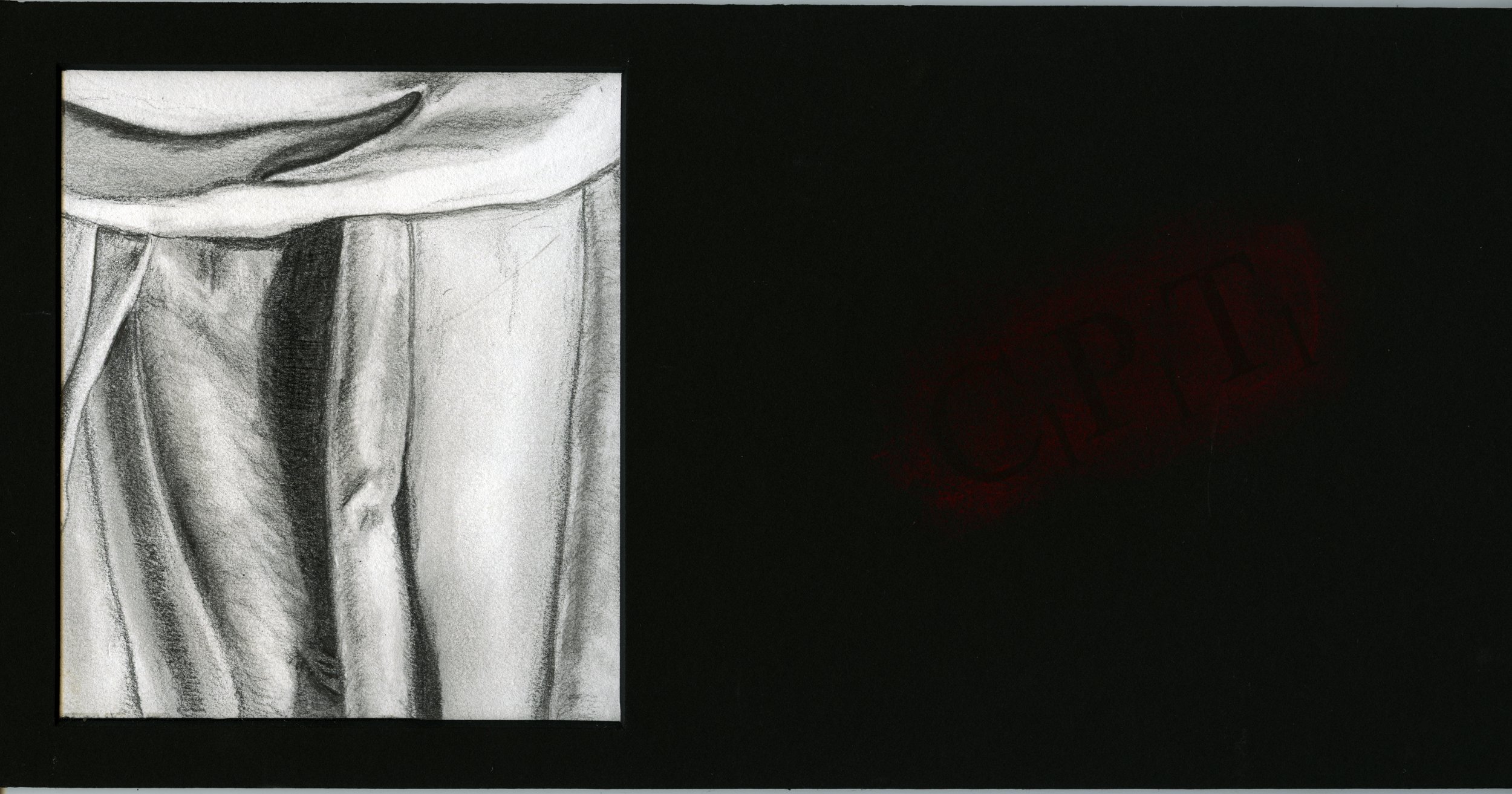

Drawings 2000 - 2010

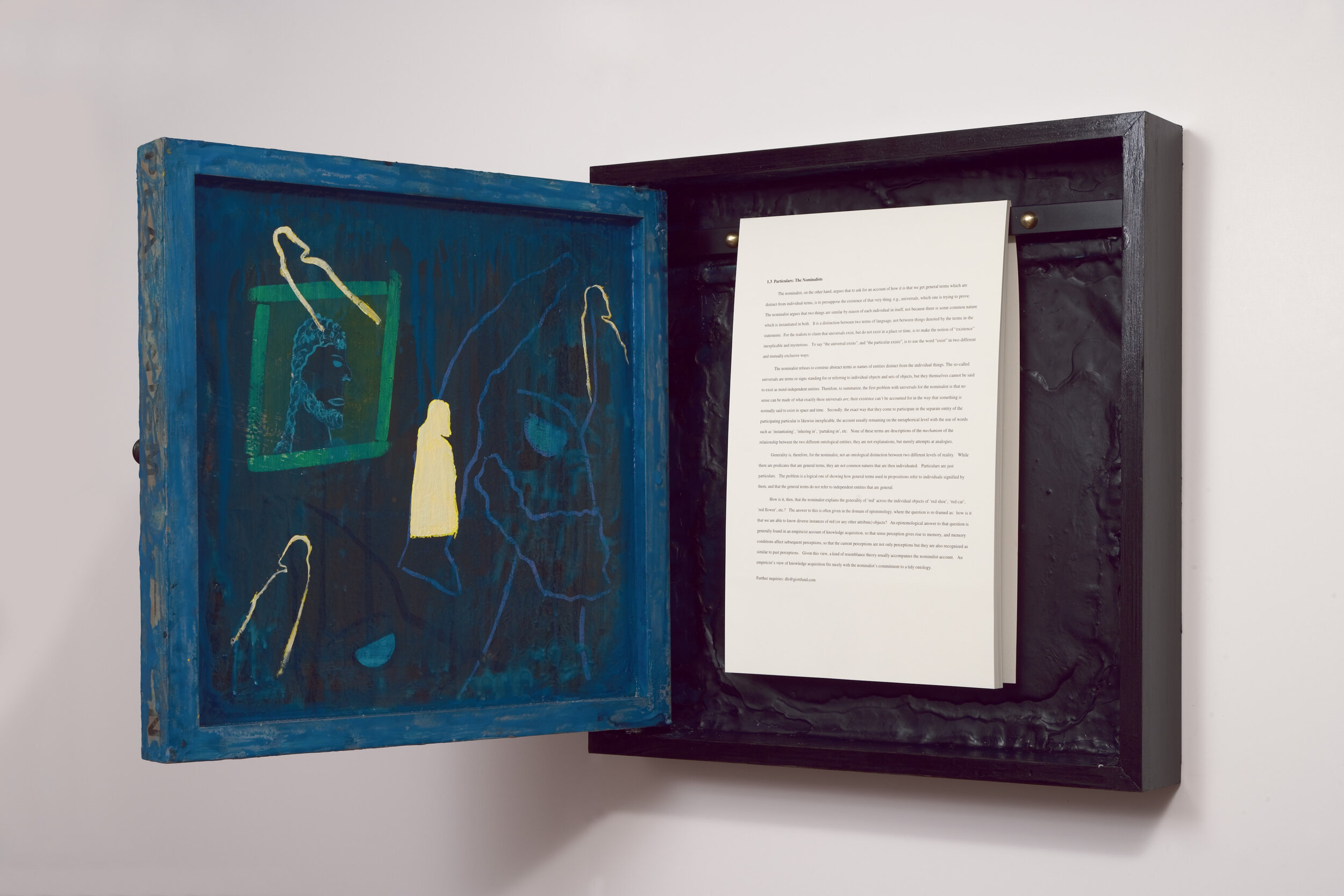

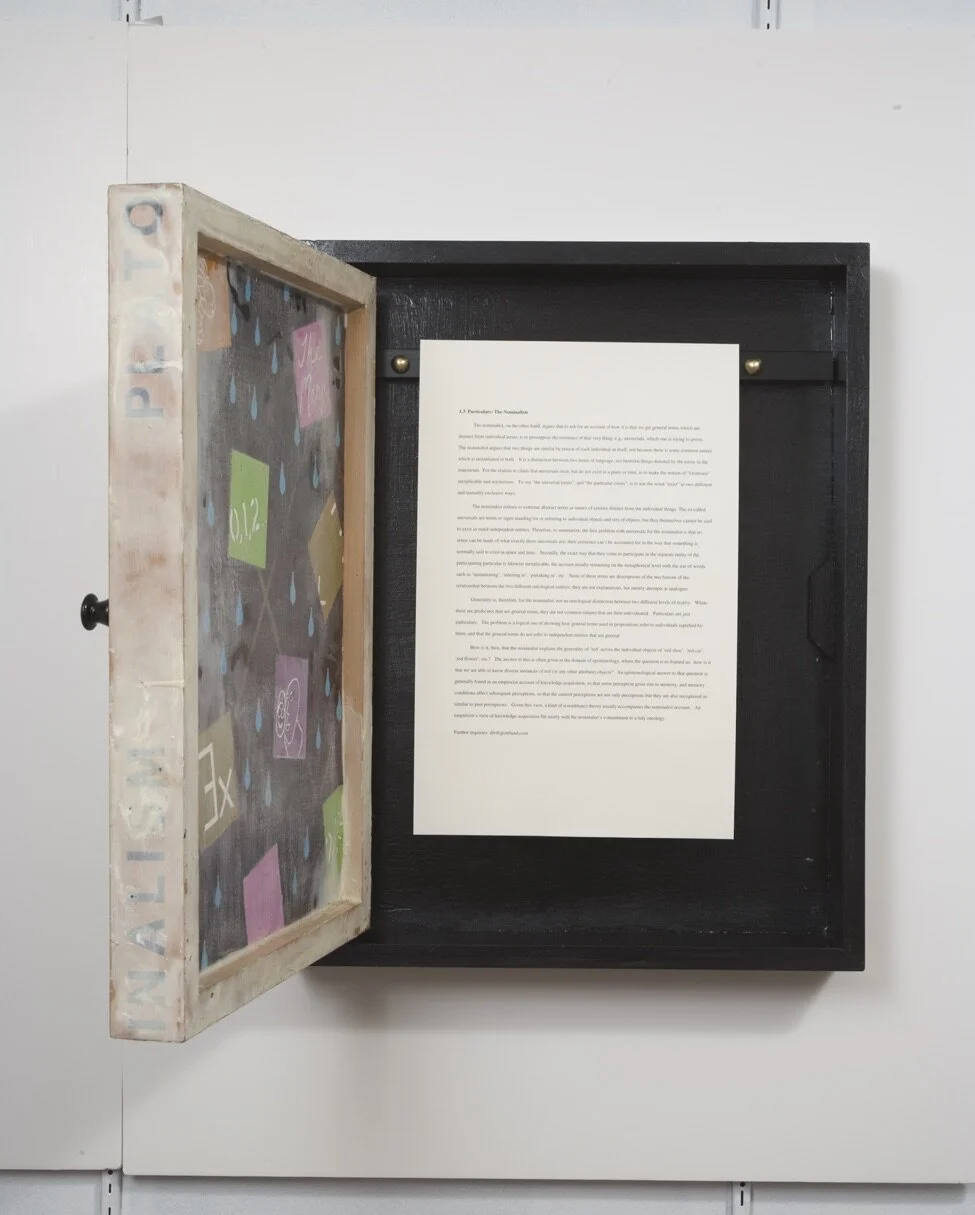

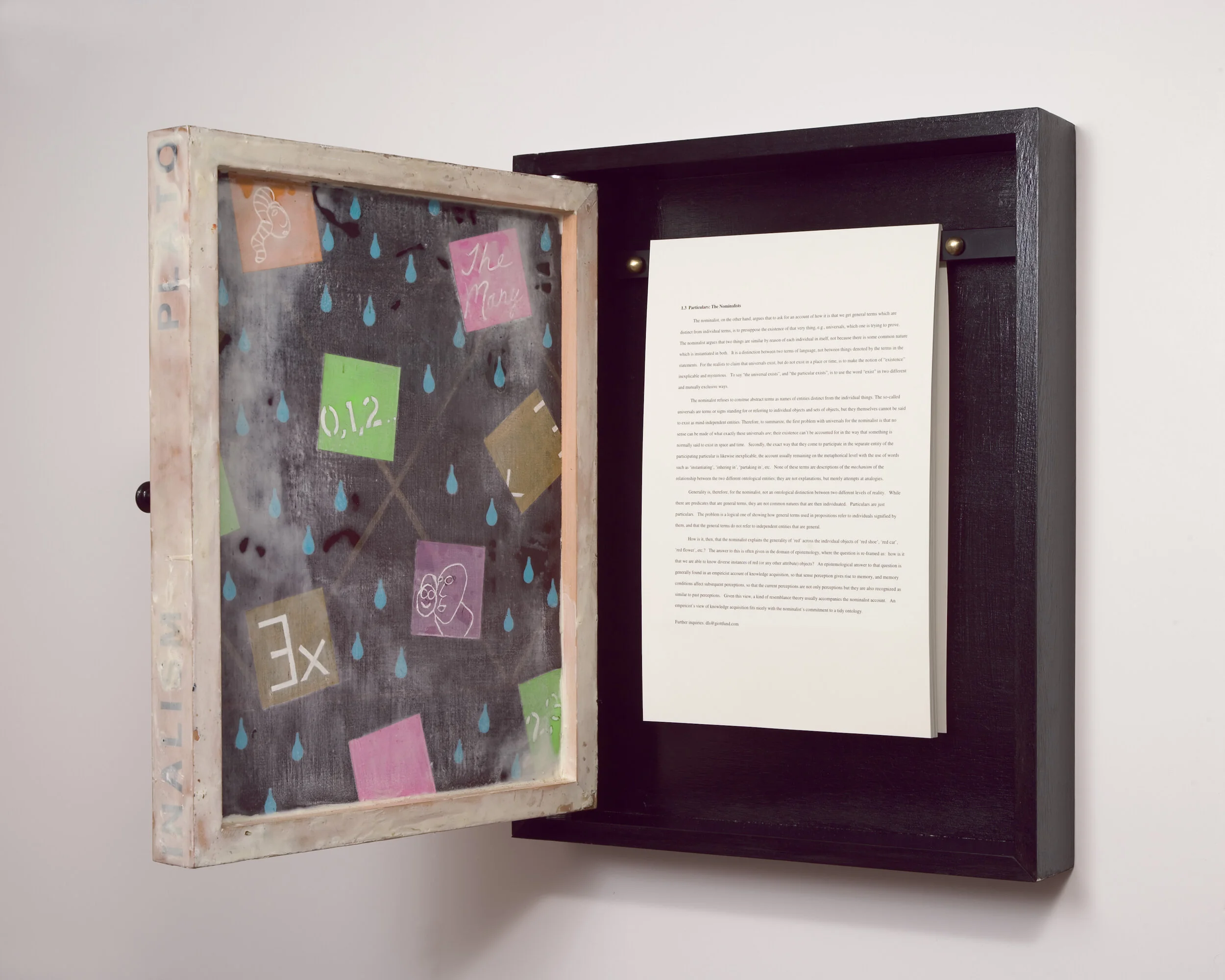

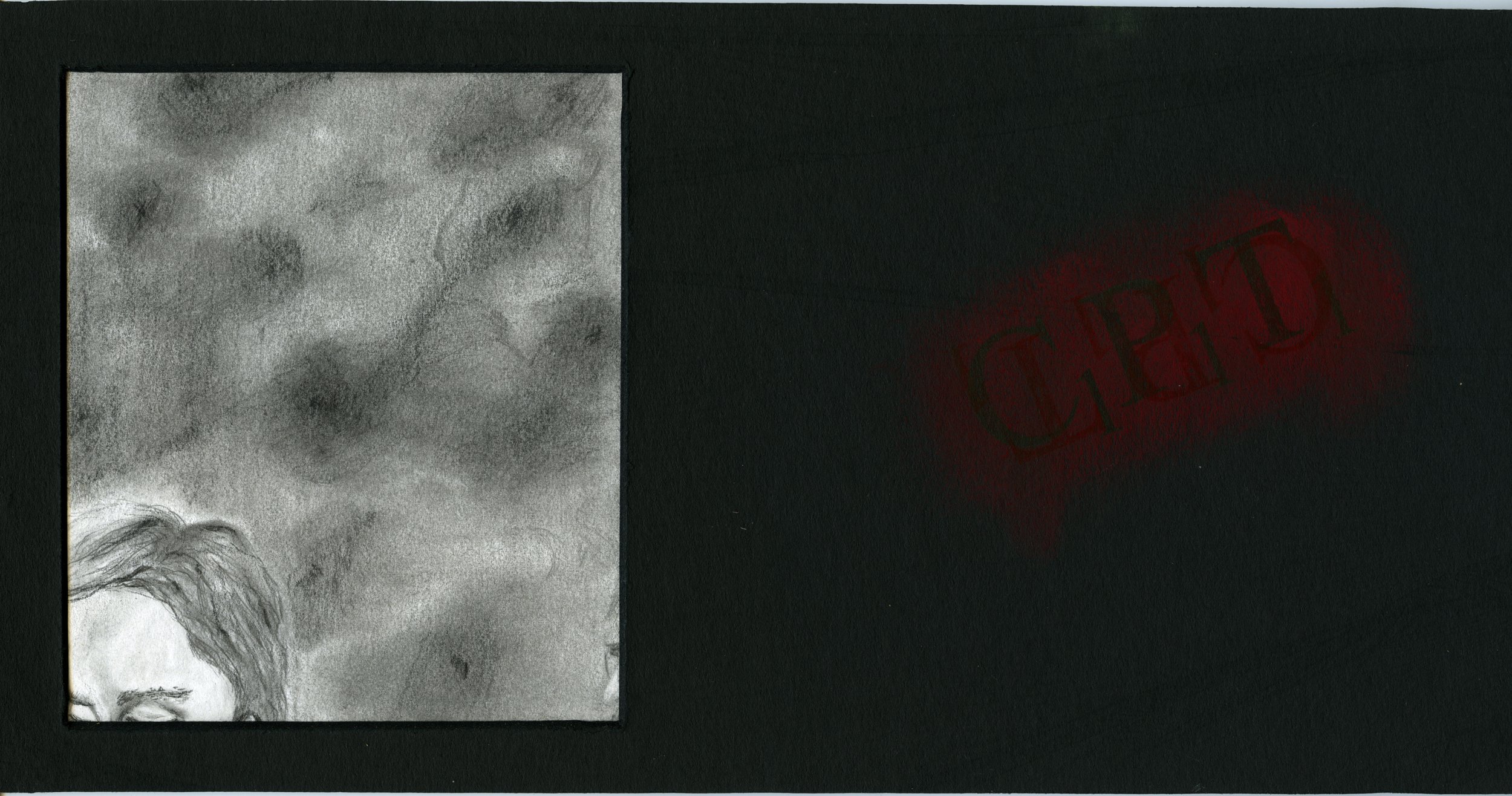

Cogito Boxes 2000 - 2010

Schemata Game

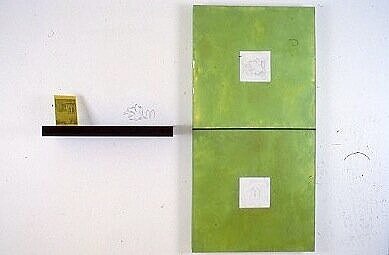

Paintings 2010 - Present

All work from 2010 until the present is incorporated into the public philosophy + socially-engaged art practice titled talkPOPc - Philosophers’ Ontological Party club. Both the writings (The Verbal) and artworks (The Visual) are included in this as two sides of the same coin.

talkPOPc began, accidentally almost, in 2012 with an exhibition I, Dena Shottenkirk, did at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. It differed from the usual exhibition in that I devoted one room to philosophers: they were the first talkPOPc Resident Philosophers, though we didn’t know it at the time. Noël Carroll (the well-known philosophy of film expert from CUNY’s Graduate Center), Lindsay Fiorelli (another aesthetician now at Claremont), David Post (technically a professor of law who was also Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s clerk, but philosophically inclined!) and a few PhD students from UPenn milled around and answered questions from those who had come to the opening. The exhibition was work I’d done around the topic of nominalism and Nelson Goodman. I had also just published a book (with Springer) on Goodman, and it was part of the exhibition. There were drawings (depicting the whole of ontology broken apart into individual qualia), a video (about Goodman), and an artists book (about the problem with Goodman’s metaphorical exemplification). All in all, a bit heady. Therefore, (clearly) the need for The Philosophers.

Amazingly so, the conversation room was buzzing with people. Milling around, everyone was asking one or another of the philosophers questions about nominalism, or Goodman, or platonism, etc. People engaged with one another. I thought, “how amazingly cool just to focus on people’s conversations.”

talkPOPc (Philosophers’ Ontological Party club) is about conversation. It is about consensus, about unity, about transcending boundaries. It is part of Philosophy as Art, Art as Philosophy.

That begins with my thoughts on a topic. After I put down my thoughts on the topic (in both “verbal” and “visual” work), we open it up to others and ask them, “What do you think about this topic?” This is when talkPOPc happens. We set up our tent, put in two chairs – one for the Resident Philosopher, and one for the participant – and we let the participant figure out what they think on the topic. Their thoughts become the podcast.

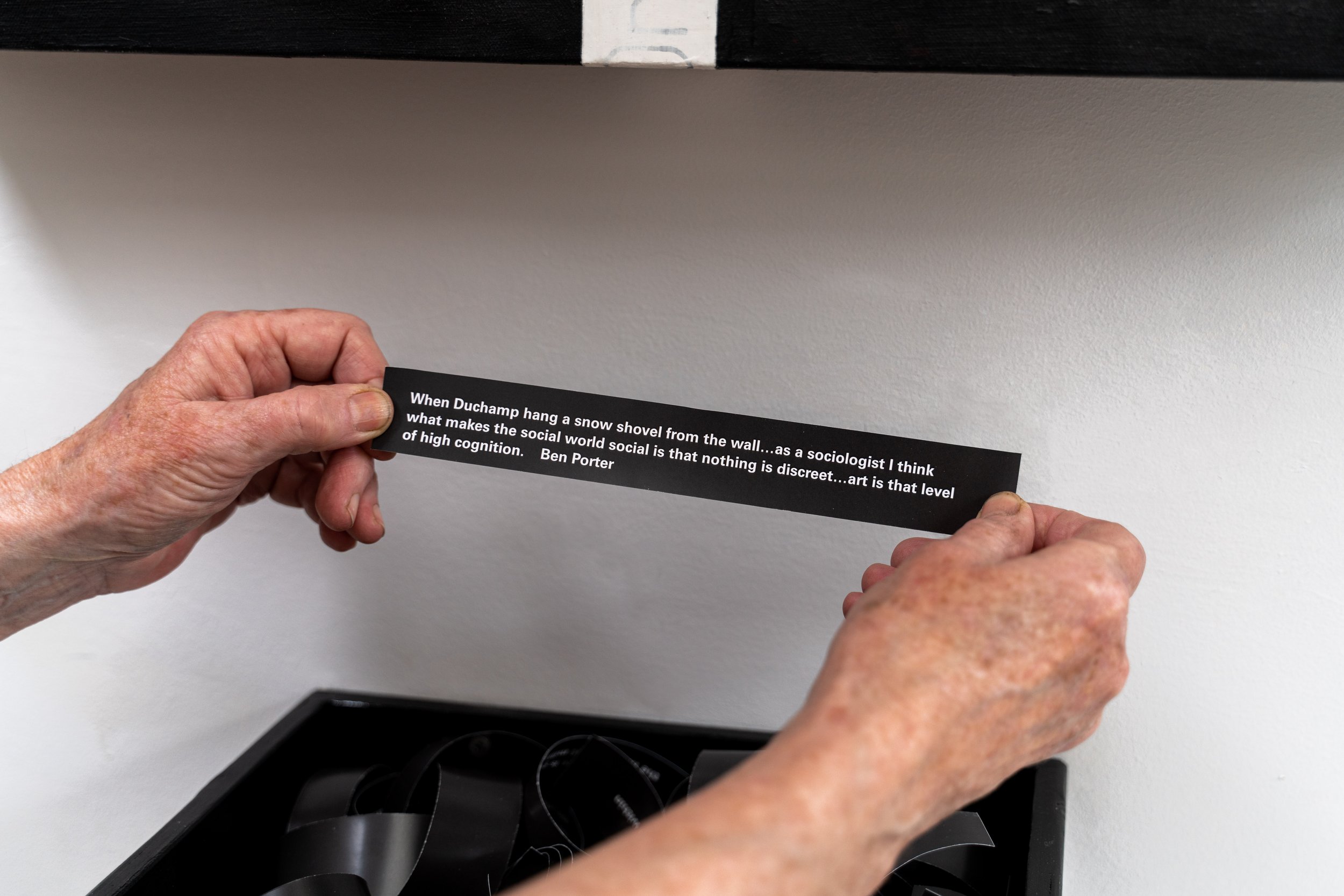

The process recycles itself. Those thoughts – of the participants’ – then reappear back into my artworks in the form of quotes. Many of the artworks that I make have a textual component, which is seen in pieces of paper (like Chinese fortune cookies!) that are rolled up and placed inside a box or the talkPOPc philosopher’s African gold hat. Those containers, filled now with slips of rolled paper both from my published works and from the participants’ quotes, hold the thoughts of many people. The rolled bits of paper can be picked up by the viewer, unrolled and read. They are bits and pieces of thoughts. This is why I call the talkPOPc artworks “ConverseThoughts”:

An art object that spills over into thought and conversation through the slippage into philosophy (both virtual and tactile), and then tunnels into real-life conversations with talkPOPc Resident Philosophers. The process therefore takes the viewer from the world of the physical art object to the world of the textual thought, to the virtual world of podcasts, puppet videos, and social media, and back to the physical world of in-person conversations. From material to immaterial, from object to transcendent thought. From art to philosophy, from philosophy to art.

Topic 1: Nominalism

The Drawings:

Topic 2: Censorship

Dena Shottenkirk Destruction of the Artifacts (2013-14) oil on canvas, , 60 in. x 72 in. x 2 1/4 in.

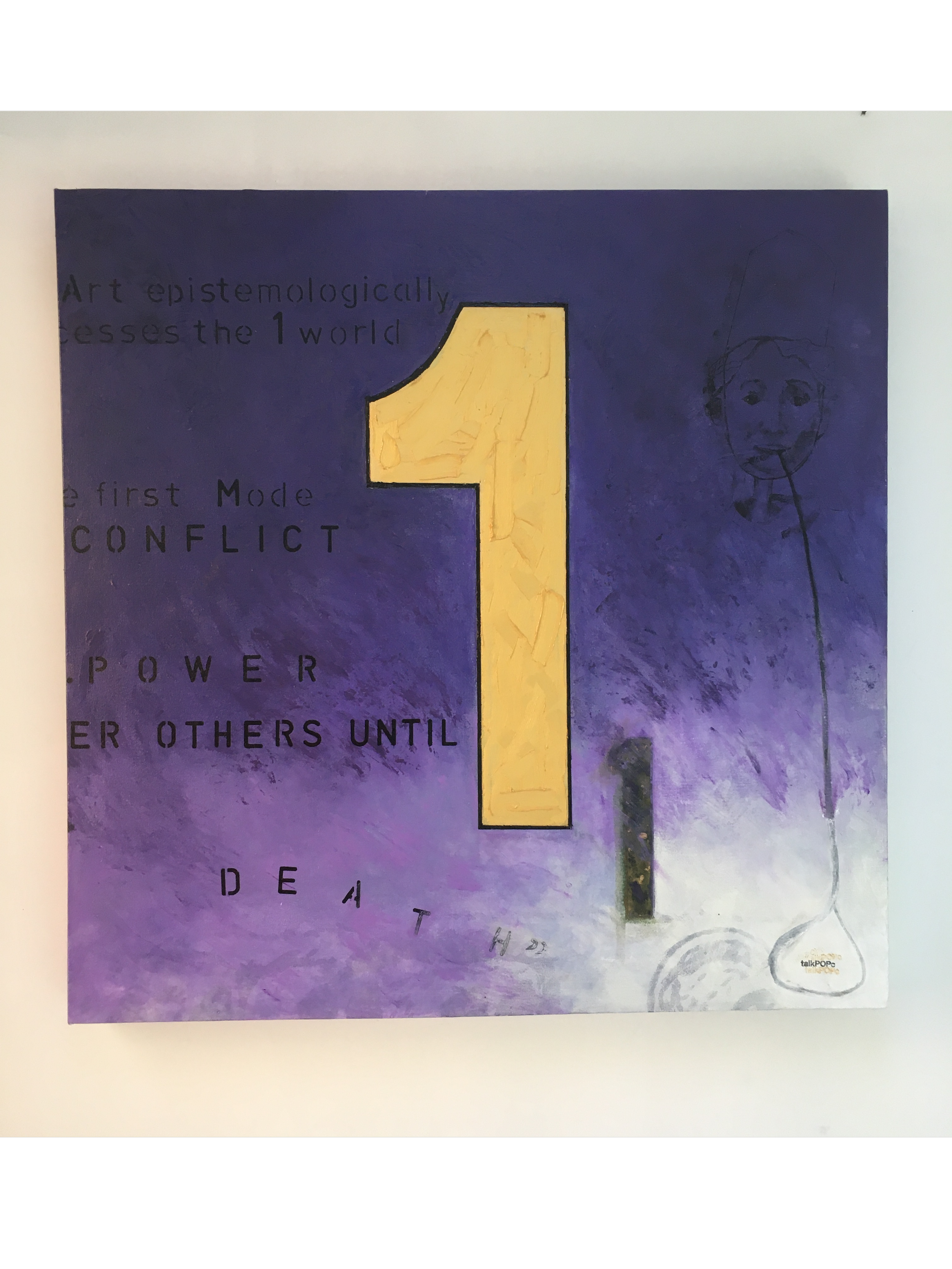

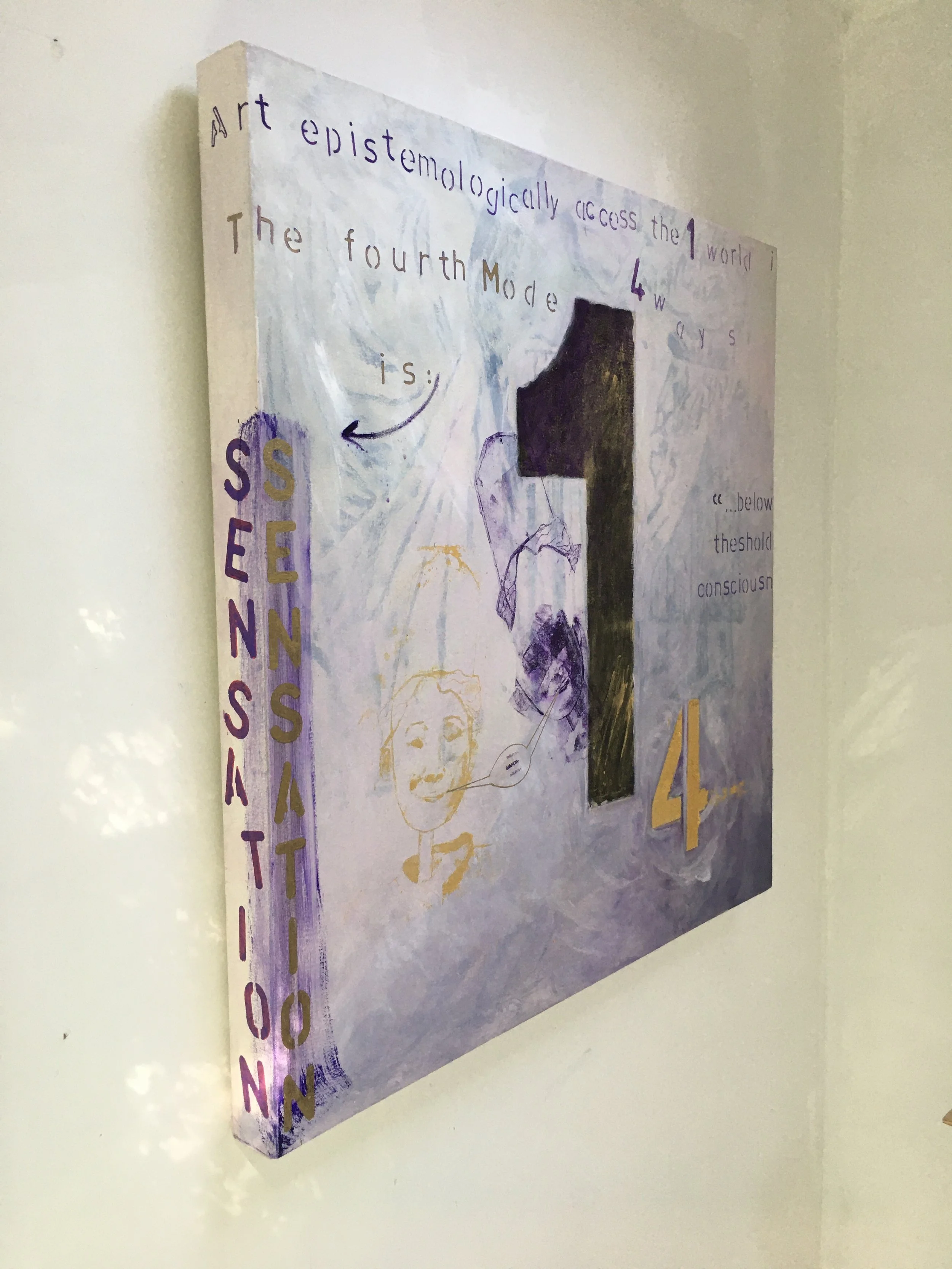

Topic 3: Art as Cognition

Neutral Monism - Art is a kind of epistemology — a kind of knowledge acquisition. It is an epistemic practice that allows us to construct a world in the face of a bombardment of vast amounts of sense data. In this I argue for an ontology that emphasizes a reality unparsed; a neutral monism. The artist (and I am here using examples of visual art, though I would apply this view across the disciplines of art) understands the world by selecting and editing from all the plethora of data that each of us experience as embodied beings…” (forthcoming Art as Cognition, Springer Verlag 2021, pg. 118)