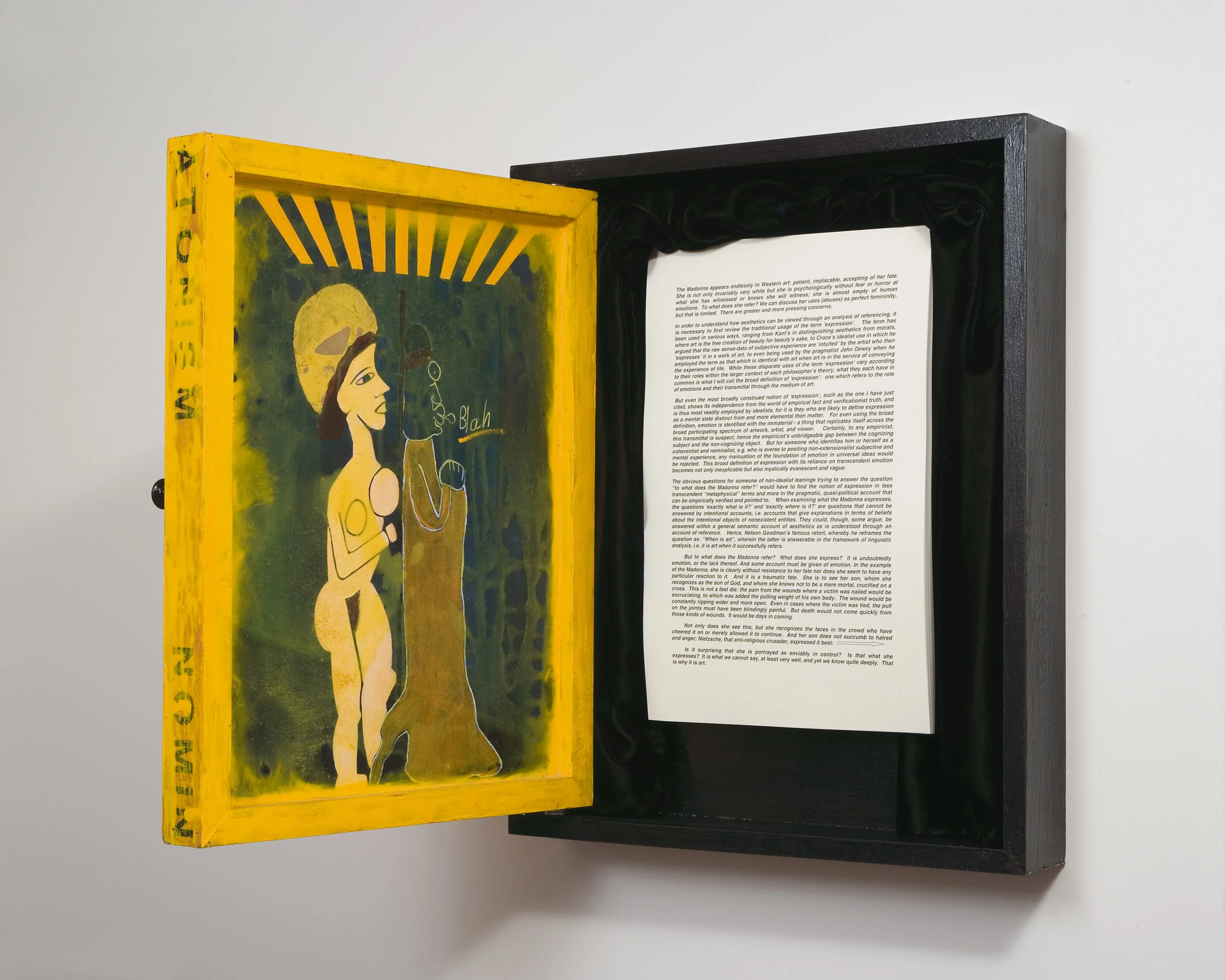

The Madonna appears endlessly in Western art: patient, implacable, accepting of her fate. She is not only invariably very white but she is psychologically without fear or horror at what she has witnessed or knows she will witness; she is almost empty of human emotions. To what does she refer? We can discuss her uses (abuses) as perfect femininity, but that is limited. There are greater and more pressing concerns.

In order to understand how aesthetics can be viewed through an analysis of referencing, it is necessary to first review the traditional usage of the term ‘expression’. The term has been used in various ways, ranging from Kant’s in distinguishing aesthetics from morals, where art is the free creation of beauty for beauty’s sake, to Croce’s idealist use in which he argued that the raw sense-data of subjective experience are ‘intuited’ by the artist who then ‘expresses’ it in a work of art, to even being used by the pragmatist John Dewey when he employed the term as that which is identical with art when art is in the service of conveying the experience of life. While these disparate uses of the term ‘expression’ vary according to their roles within the larger context of each philosopher’s theory, what they each have in common is what I will call the broad definition of ‘expression’: one which refers to the role of emotions and their transmittal through the medium of art.

But even the most broadly construed notion of ‘expression’, such as the one I have just cited, shows its independence from the world of empirical fact and verificationist truth, and is thus most readily employed by idealists, for it is they who are likely to define expression as a mental state distinct from and more elemental than matter. For even using the broad definition, emotion is identified with the immaterial - a thing that replicates itself across the broad participating spectrum of artwork, artist, and viewer. Certainly, to any empiricist, this transmittal is suspect; hence the empiricist’s unbridgeable gap between the cognizing subject and the non-cognizing object. But for someone who identifies him or herself as a coherentist and nominalist, e.g. who is averse to positing non-extensionalist subjective and mental experience, any insinuation of the foundation of emotion in universal ideas would be rejected. This broad definition of expression with its reliance on transcendent emotion becomes not only inexplicable but also mystically evanescent and vague.

The obvious questions for someone of non-idealist leanings trying to answer the question “to what does the Madonna refer?” would have to find the notion of expression in less transcendent “metaphysical” terms and more in the pragmatic, quasi-political account that can be empirically verified and pointed to. When examining what the Madonna expresses, the questions ‘exactly what is it?’ and ‘exactly where is it?’ are questions that cannot be answered by intentional accounts, i.e. accounts that give explanations in terms of beliefs about the intentional objects of nonexistent entities. They could, though, some argue, be answered within a general semantic account of aesthetics as is understood through an account of reference. Hence, Nelson Goodman’s famous retort, whereby he reframes the question as: “When is art”, wherein the latter is answerable in the framework of linguistic analysis, i.e. it is art when it successfully refers.

But to what does the Madonna refer? What does she express? It is undoubtedly emotion, or the lack thereof. And some account must be given of emotion. In the example of the Madonna, she is clearly without resistance to her fate nor does she seem to have any particular reaction to it. And it is a traumatic fate. She is to see her son, whom she recognizes as the son of God, and whom she knows not to be a mere mortal, crucified on a cross. This is not a fast die: the pain from the wounds where a victim was nailed would be excruciating, to which was added the pulling weight of his own body. The wound would be constantly ripping wider and more open. Even in cases where the victim was tied, the pull on the joints must have been blindingly painful. But death would not come quickly from those kinds of wounds. It would be days in coming.

Not only does she see this, but she recognizes the faces in the crowd who have cheered it on or merely allowed it to continue. And her son does not succumb to hatred and anger; Nietzsche, that anti-religious crusader, expressed it best:

Is it surprising that she is portrayed as enviably in control? Is that what she expresses? It is what we cannot say, at least very well, and yet we know quite deeply. That is why it is art.