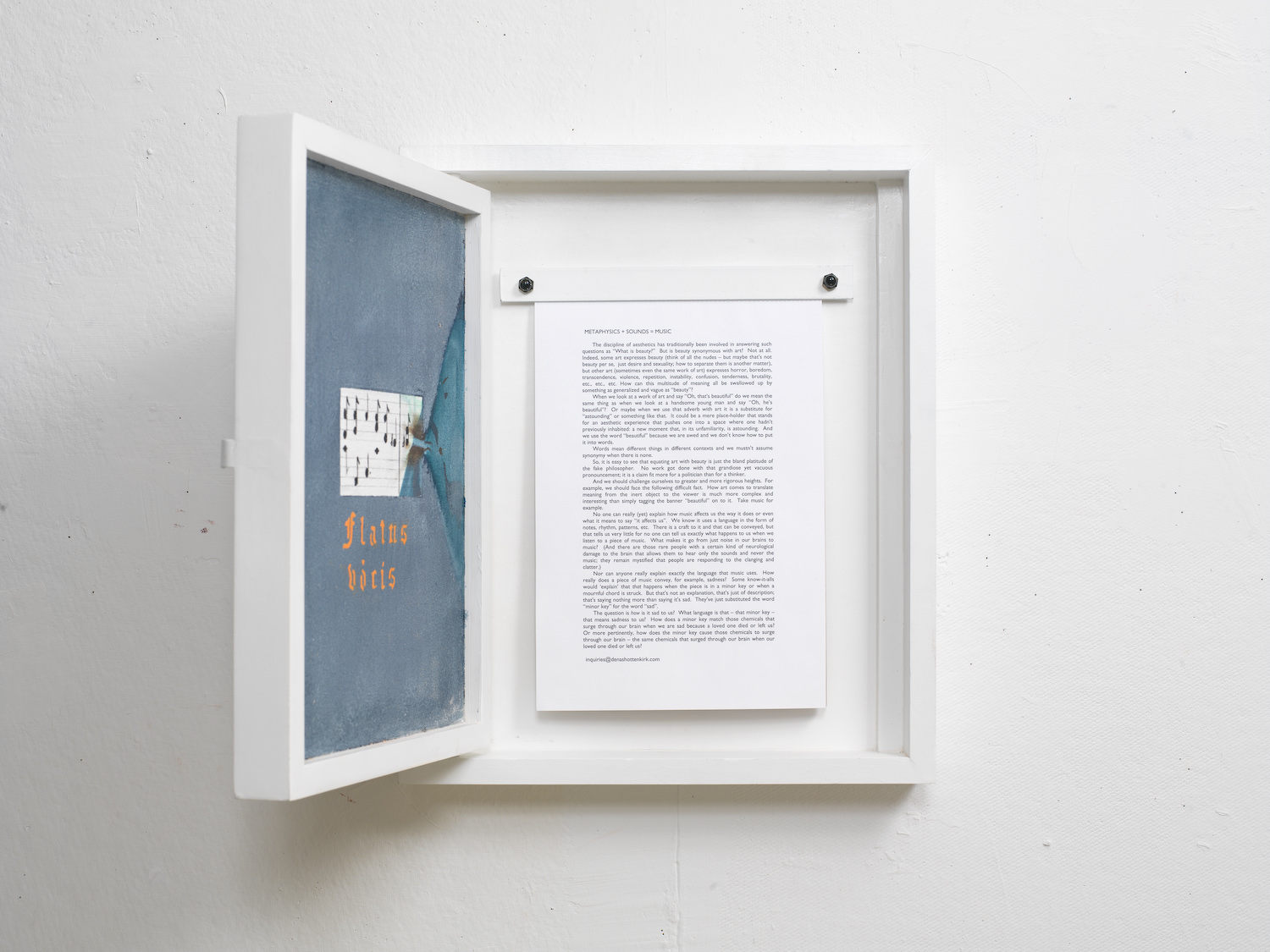

METAPHYSICS + SOUNDS = MUSIC

The discipline of aesthetics has traditionally been involved in answering such questions as “What is beauty?” But is beauty synonymous with art? Not at all. Indeed, some art expresses beauty (think of all the nudes – but maybe that’s not beauty per se, just desire and sexuality; how to separate them is another matter), but other art (sometimes even the same work of art) expresses horror, boredom, transcendence, violence, repetition, instability, confusion, tenderness, brutality, etc., etc., etc. How can this multitude of meaning all be swallowed up by something as generalized and vague as “beauty”?

When we look at a work of art and say “Oh, that’s beautiful” do we mean the same thing as when we look at a handsome young man and say “Oh, he’s beautiful”? Or maybe when we use that adverb with art it is a substitute for “astounding” or something like that. It could be a mere place-holder that stands for an aesthetic experience that pushes one into a space where one hadn’t previously inhabited: a new moment that, in its unfamiliarity, is astounding. And we use the word “beautiful” because we are awed and we don’t know how to put it into words.

Words mean different things in different contexts and we mustn’t assume synonymy when there is none.

So, it is easy to see that equating art with beauty is just the bland platitude of the fake philosopher. No work got done with that grandiose yet vacuous pronouncement; it is a claim fit more for a politician than for a thinker.

And we should challenge ourselves to greater and more rigorous heights. For example, we should face the following difficult fact. How art comes to translate meaning from the inert object to the viewer is much more complex and interesting than simply tagging the banner “beautiful” on to it. Take music for example.

No one can really (yet) explain how music affects us the way it does or even what it means to say that it affects us. We know it uses a language in the form of notes, rhythm, patterns, etc. There is a craft to it and that can be conveyed, but that tells us very little for no one can tell us exactly what happens to us when we listen to a piece of music. What makes it go from just noise in our brains to music? (And there are those rare people with a certain kind of neurological damage to the brain that allows them to hear only the sounds and never the music; they remain mystified that people are responding to the clanging and clatter.)

Nor can anyone really explain exactly the language that music uses. How exactly does a piece of music convey, for example, sadness? Some know-it-alls would ‘explain’ that that happens when the piece is in a minor key or when a mournful chord is struck. But that’s not an explanation, that’s just of description; that’s saying nothing more than saying it’s sad. They’ve just substituted the word “minor key” for the word “sad”.

The question is how is it sad to us? What language is that – that minor key – that means sadness to us? How does a minor key match those chemicals that surge through our brain when we are sad because a loved one died or left us? Or more pertinently, how does the minor cause those chemicals to surge through our brain – the same chemicals that surged through our brain when our loved one died or left us?